Raphael Merven, Department of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Montpellier, France

Chandani Appadoo & F.B. Vincent Florens, Tropical Island Biodiversity, Ecology and Conservation Pole of Research, Department of Biosciences and Ocean Studies, Faculty of Science, University of Mauritius

Pricila Iranah, Department of Biology, University of Nebraska at Kearney, United States of America

Mangroves are coastal ecosystems developing in tropical and subtropical areas of the world, alongside coral reefs and seagrass beds. They ensure essential ecological functions, such as being a nursery for juvenile fish, sequestering carbon and mitigating tsunamis and cyclones. Nevertheless, due to anthropogenic stresses such as coastal landfill, pollution and clearing for aquaculture, mangrove ecosystems showcase one of the major impacts of anthropogenic change, with a global loss of 1.04 million ha between 1990 and 2020. This dramatic situation even brought scientists to consider the prospect of their disappearance worldwide within a century.

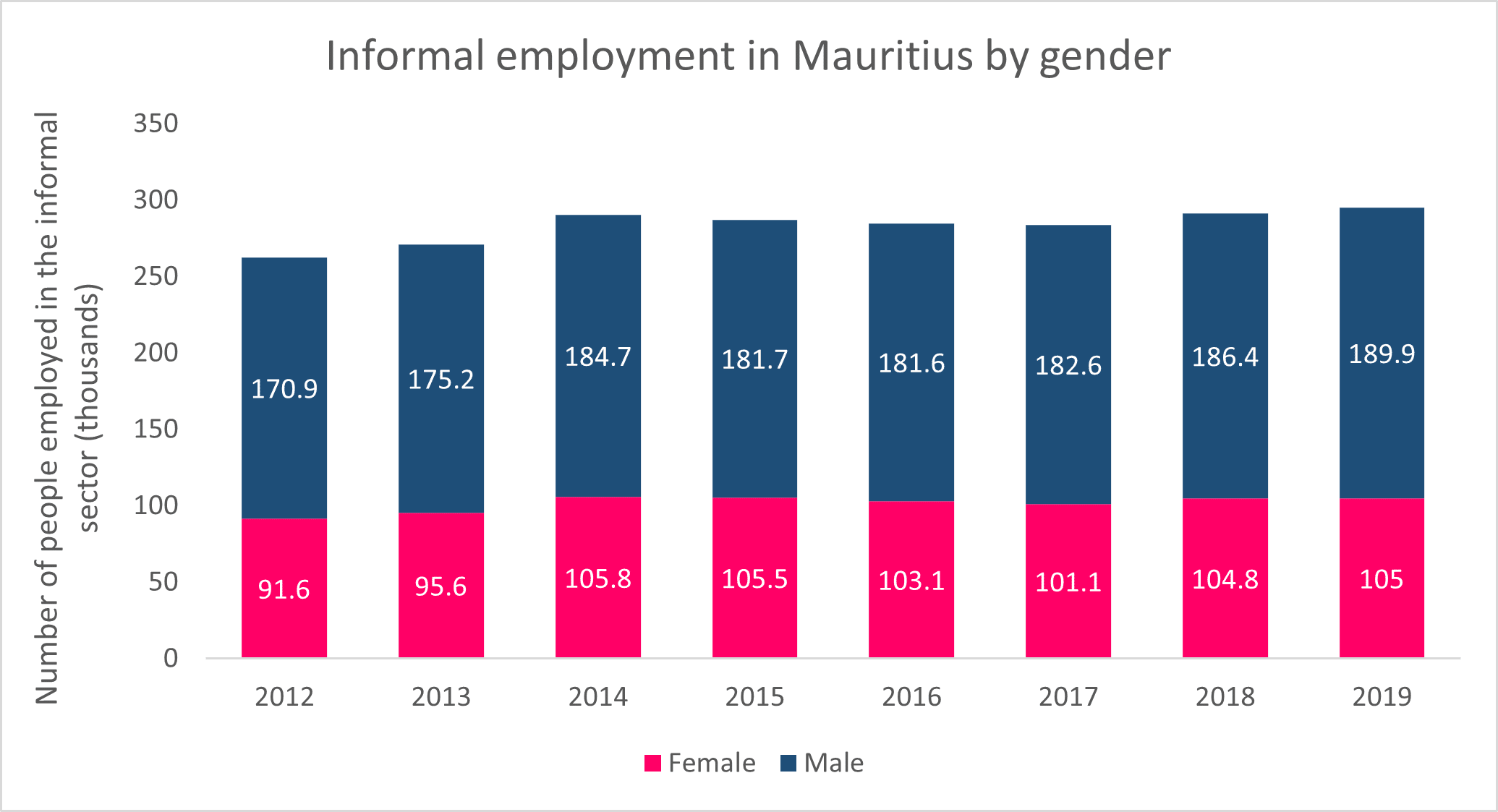

Mangroves support local communities by providing forest goods, supporting marine productivity and carrying cultural values. In Mauritius however, mangroves’ socio-economic and cultural importance is poorly referenced. On the island, they are fishing grounds for artisanal fisheries and mangrove plants have a historical use in traditional medicine, but these practices have declined due to lifestyle, income changes, and environmental legislation.

On the other hand, Mauritian mangroves are in the middle of social and environmental tensioning. While coastal development and tourism activities have brought employment and economic growth, they have also exerted increasing pressure on marine and intertidal ecosystems, especially wetlands and mangroves. Out of 209 coastal wetlands surveyed in 2011, most were exhibiting edge-related disturbances and more than half were fragmented. Another study reported that twelve out of the fourteen Environmentally sensitive Areas (ESAs) in Mauritius are at risk of degradation, with six coastal and marine ESAs types, including mangroves, being exposed to urban expansion and resource over-use.

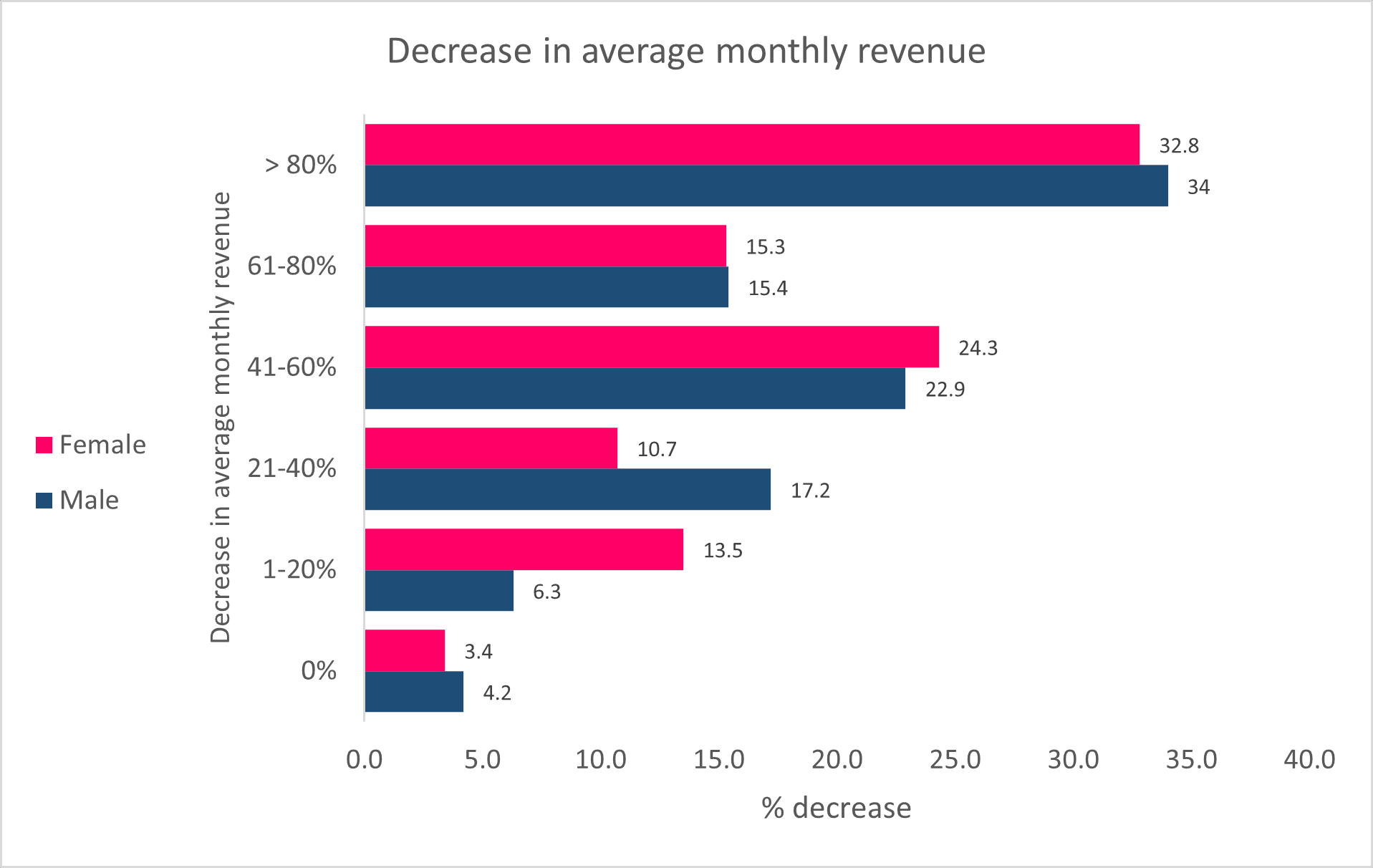

Compounding development impacts, communities on the east and southeast coasts of Mauritius experienced an ecological disaster when the MV Wakashio, a bulk carrier vessel, ran aground on coral reefs and released some 1,000 tons of oil into the region’s lagoon on the 6th of August 2020, with a portion of that oil depositing on rocky shorelines and in mangrove forests. While the impacts of the global COVID-19 pandemic were already affecting the coastal areas relying on tourism and fisheries, this oil spill is considered by many as the worst ecological disaster Mauritius has ever experienced since its independence in 1968, and has exacerbated socio-economic difficulties of many households of the region.

In this multiple crisis context, we investigated the socio-economic and cultural importance of mangroves for coastal communities in Mauritius, with a focus on the eastern coastal areas and using an Ecosystem Services (ES) framework. Building our approach on the criticism faced by the ES framework, mainly for its anthropocentric view of nature and its monetary-centred evaluation methods, our study also encompasses the linkage between local socio-economic context, ecosystem services dependency and the impact of internal and external events.

More specifically, we collected data through a household survey in four villages on the east-southeast coast of Mauritius: Bambous Virieux and Bois des Amourettes (grouped as the South-East region), Trou d’Eau Douce and Poste de Flacq (refer to Figure 1). These villages all presented numerous mangrove patches and fishing areas, and they were differently impacted by the Wakashio oil spill in respect to their distance from the oil spill site, providing relevant data for analytical comparison. In all villages, the local lifestyle is closely associated with fisheries and tourism. Around 300 households were investigated in person following a structured questionnaire approach, where we collected information on:

-

- respondent’s demographics;

- their perception of the impacts of the recent crises on their socio-economic situation;

- their activities related to mangroves and fisheries;

- their perception on the status and changes within mangrove ecosystems.

Mangroves Ecosystem Services in Mauritius

We found that Mauritian mangroves, despite occupying only 0.07% of the island surface, support coastal communities with a wide range of services. Ecosystem services provided by mangroves to the studied villages play a major role in terms of cultural values, food security, fisheries support, income generation, human health and well-being, and intangible heritage value.

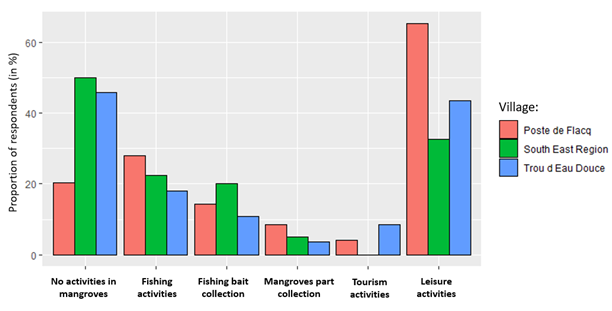

Recreational activities are the most cited mangrove-based activities in all villages (Figure 1), and therefore reveal a previously unreported cultural importance of mangroves on the east coast of Mauritius. Mangroves support leisure activities, like picnicking, leisure fishing or playing, as well as various social and cultural activities such as strolls, discussions and festivities. Even if not represented in the recreational activities survey results, the spiritual values associated to mangroves are physically embodied in the various shrines and other religious structures found in or near mangroves.

The high proportion of respondents having recreational activities in mangroves suggests that even greater cultural services are provided by mangroves, as stated in other studies worldwide. Aesthetic values encompassed by mangrove landscapes likely play a role in the cultural services provided by the ecosystem, but more importantly support tourism for hotel scenery and tourist operators. Seafood collection in mangroves is practised by roughly a quarter of all respondents, and more than 10% of each village respondents collect fishing bait in mangroves, highlighting the crucial role of this ecosystem for local fisheries and nutritional support.

Mangroves plant parts collection is a minor activity in the surveyed area, and is practiced mainly for medicinal uses. The minimal use of mangrove plant parts in Mauritius is likely due to factors that include environmental changes and changes in lifestyle, in addition to the legislation meant to prevent such harvests as a means to protect remaining mangrove patches.

Socio-economic drivers modulate dependency on mangroves

To investigate communities’ dependency on mangroves ecosystem services, we performed statistical analysis coupling households’ socio-economic data and ecosystem services provided by mangroves to each household. Analytical models were used to understand the importance of each ecosystem services and to link them to household’s socio-economic situation. We found that nearly two thirds of all respondents have low to high dependency on mangroves ecosystem services. Given that this ecosystem only covers small patches in three out of four surveyed villages, our findings suggest a disproportionate contribution of mangroves to human well-being and livelihoods where they occur in Mauritius.

We also found that dependency on mangrove ecosystem services is strongly influenced by socio-economic parameters. Lower monthly incomes and the lack of assets like land, increase the chances for an individual to have a stronger level of dependency, as does a higher household size. On the other hand, higher education levels and being at least 60 years old increases the chances for individuals to have no dependencies on mangrove ecosystem services. These results suggest that limited livelihood opportunities lead to a stronger dependency on mangroves ecosystem services and natural resources.

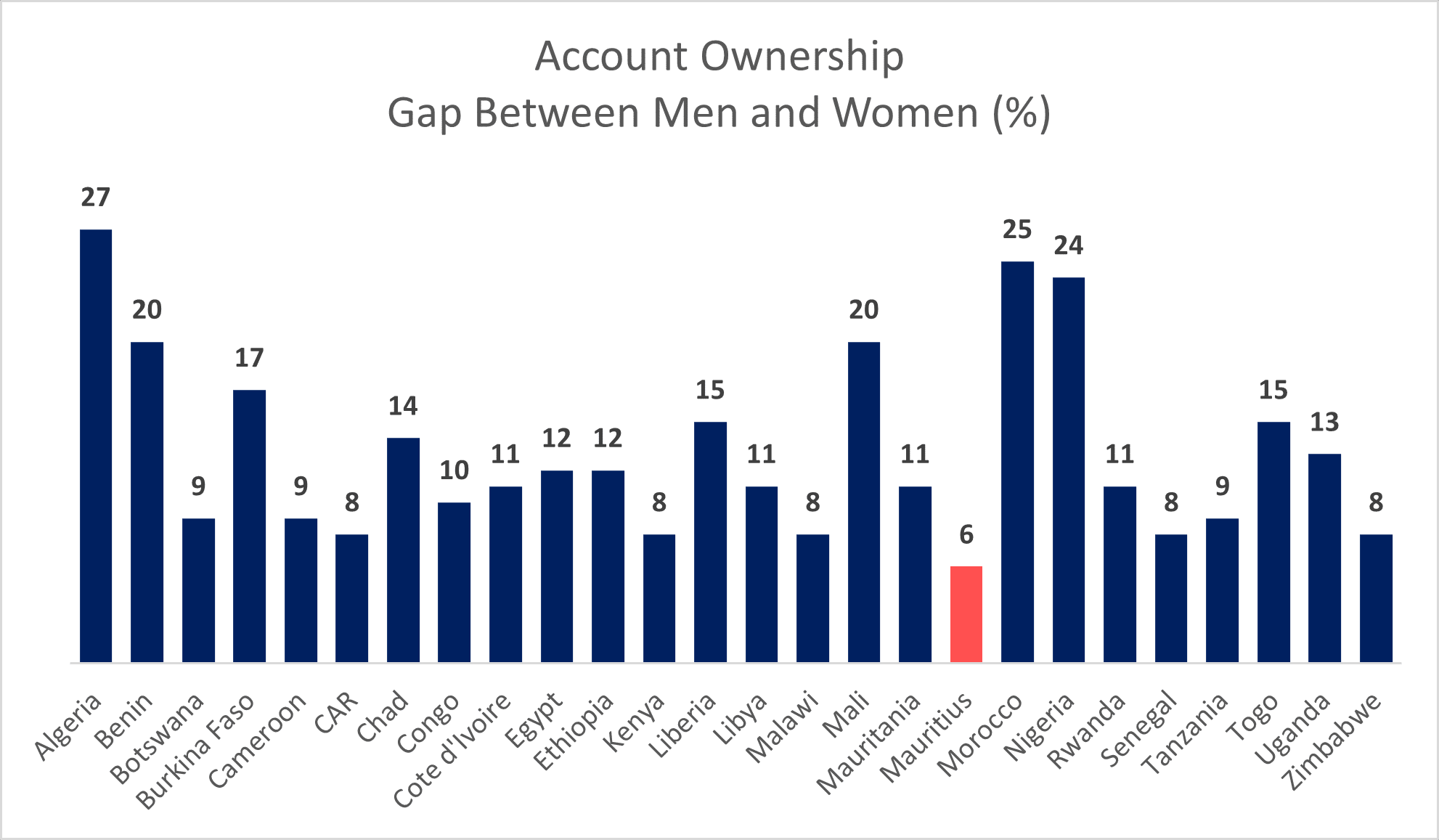

Women have a higher chance to experience higher levels of dependency on mangrove ecosystem services as compared to men. This result may be explained by a higher preponderance of women collecting seafood other than fish in the east and south-east coast villages of Mauritius, a practice strongly associated with mangrove fisheries. In parallel to subsistence or artisanal mangrove-based fishing or seafood collection, women lack recognition for their contribution to the fishery sector, with only 35 out of 1,902 registered fishers listed as women.

Environmental changes and management implications

The economic losses felt as a consequence of the Wakashio oil spill and the COVID-19 crisis have resulted in the strong dependence on mangroves ecosystem services. These findings therefore suggest that mangrove ecosystems have a critical role in mitigating socio-economic and ecological crises in the studied area. Indeed, previous studies concur on the importance of ecosystem services during the COVID-19 pandemic, supporting our findings that mangroves are essential for local livelihoods. In return, the Wakashio oil spill had severe impacts on mangrove ecosystem and their related services.

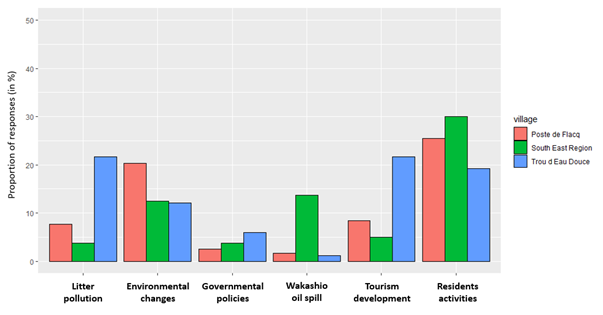

When interrogating respondents in our study sites, the oil spill is the second highest ranked perceived reason for mangrove cover decrease in south-east villages. On the other hand, residents in both Poste de Flacq and Trou d’Eau Douce predominantly attributed declines in mangrove cover to residents’ activities and tourism development respectively. Globally, over half of the respondents perceived a decline in mangrove cover and 70% perceive a decline in seafood quantity in all villages. These results, even if influenced by subjective risk perception when facing extreme events, attest to a local apprehension regarding loss of mangrove ecosystems and their associated services at the national scale.

Mangroves provide multiple underreported provisioning and cultural services to surrounding inhabitants and have a direct importance in building local and regional adaptation and resilience to global changes. Socio-economic, ecological and climatic crises are expected to worsen rapidly in frequency and intensity in the coming decades, and SIDS like Mauritius, which are disproportionally vulnerable to these events, have an urgent need to implement mitigation and adaptation strategies for coastal areas both because they harbour centres of economic importance (ports, tourism) and are often home to marginalised populations. Households that are the most vulnerable to crisis and mangrove degradation, as reported locally and as this present study suggests, are the ones with limited livelihood opportunities. Management approaches such as nature-based solutions and co-management may help take into account resource users’ and local inhabitants’ constraints and needs in management policies, as well as mitigating the impacts of multiple crises through co-constructed resilience scenario implementation.

Main photo by David Clobe on Unsplash.

All pictures © copyright authors.

Charles Telfair Centre is an independent nonpartisan not for profit organisation and does not take specific positions. All views, positions, and conclusions expressed in our publications are solely those of the author(s).