Dr Elena Nikolova, Zayed University, United Arab Emirates (UAE)

Although education is a basic human right, in many developing countries, children with disabilities are excluded from formal education at great cost to themselves and society. In a new book chapter, we investigate the barriers to inclusive education for children with disabilities in Ethiopia, Burkina Faso and Niger, which are three of the world’s poorest countries. Despite legislative commitments to advance education for children with disabilities, we find that children with disabilities are marginalized in educational settings, which negatively affect their empowerment, earnings, and quality of life. Our findings for these three countries have relevance for the Indian Ocean region including Mauritius.

What is disability?

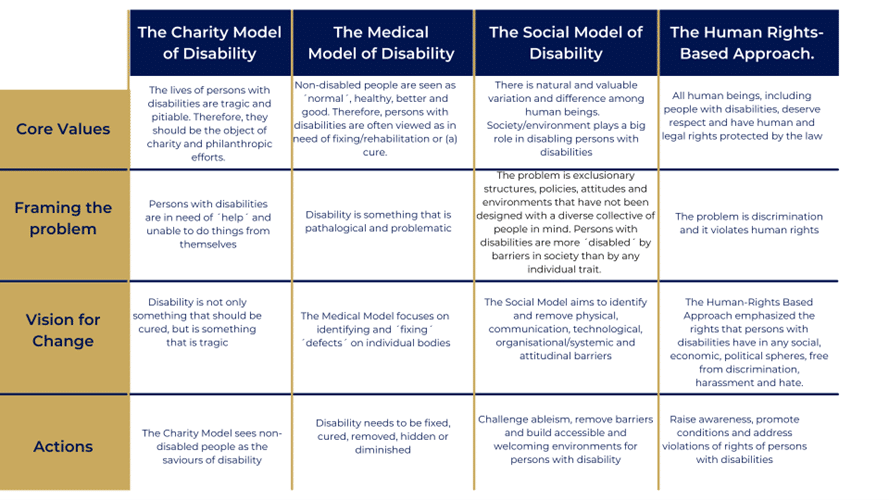

There are four different views of disability, which are summarized in Figure 1 below. According to the charity model of disability, the disabled are victims who depend on the help of others, and therefore, should be grateful for any donations that come their way. According to the medical model of disability, persons with disabilities (including children with disabilities) are identified as ‘disabled’ because they have visible impairments or have been medically diagnosed as such by a medical practitioner. According to this model, emphasis should be put on medical and technological assistance so that those with disabilities can become ‘normal’ again. Conversely, the social model of disability moves away from the narrow medical focus on curing impairment and emphasizes removing legal barriers and including people with disabilities in all spheres of life at the family, community, and societal levels. Finally, the human rights approach builds on the social model by going beyond anti-discrimination policy and civil rights reforms, to encompass civil and political as well as economic, social, and cultural rights. Our chapter utilizes the human rights model in the analysis.

Findings

Around the world, as many as half of the 65 million learners of primary and secondary school age with disabilities are out of school (data from 2015). According to the 2011 World Report on Disability, 6% of children under the age of 14 in Africa have either moderate or severe disabilities, and less than 10% of all children with disabilities in this age range, are attending school. For Ethiopia, Niger, and Burkina Faso, the estimates for the overall prevalence of persons with disabilities, and children with disabilities specifically, range widely. Similarly, there is no single, consistent source of data on educational enrolment and attainment among children with disabilities. While data availability, reliability, and comparability across the three study countries are a challenge, the available evidence points to high levels of exclusion and marginalization of children with disabilities in each country.

To better understand barriers to inclusive education for children, we conducted 44 semi-structured Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) (14 in Ethiopia, 11 in Niger, and 15 in Burkina Faso, and four with international partner organizations headquartered in Europe that operate in the three countries). The key informants interviewed include representatives of children with disabilities, inclusive education focal persons within governments, organizations of persons with disabilities, and NGOs implementing inclusive education projects.

Our analysis reveals that while the three countries have good legislative frameworks on educating children with disabilities and some assistance from international partners, important challenges remain. At the school level, challenges include low quality and few resources to support special schools, lack of integration of special schools with mainstream schools, and lack of trained teachers. At the community level, there is a lack of community and parental awareness of the options available to children with disabilities, low environmental infrastructure, and prejudice against people with disabilities. Lack of data prevents governments and donors from understanding the scope of the problem and from working on appropriate solutions integrating children with disabilities in education.

In addition, the key informants identified several cross-cutting challenges to educating children with disabilities, which are as follows:

-

- Family level: Negative parental attitudes towards disability, lack of awareness of education opportunities and family poverty were all challenges identified in our data.

- School level: There are inadequate school facilities, lack of accessible infrastructure, lack of educational materials, inadequate supply of teachers and insufficient teacher training.

- Community level: A combination of existing factors include negative societal attitudes towards disability, lack of accessible forms of transportation to/from schools, insecurity and violence, including war, terrorism, and intracommunal conflict.

- System level: Issues identified relate to a lack of reliable data for understanding the situation, and for monitoring progress, inadequate attention to disability issues in government policy & programs, poor coordination across different government bodies involved in disability inclusion and education, and lack of government resources for education generally.

Policy solutions

In the chapter, we highlight several programs aimed at tackling the educational exclusion of children with disabilities which can serve as a blueprint for more large-scale interventions in the three countries and beyond. In Niger, the government is collaborating with international NGOs and bilateral donors for the introduction of an inclusive education module in the Ministry of Education’s teacher training program, through the project Promotion d’un modèle d’éducation inclusive à Maradi [Promoting an Inclusive Education Model in Maradi – PMEI]. The PMEI project, together with another project (Agir pour la pleine participation des enfants handicapés par l’éducation [Working Towards the Full Participation of Children with Disabilities through Education – APPELH]), have trained over 450 teachers and school principals on the inclusion of children with disabilities. In Ethiopia, the Atse Zereyakob primary School in Debre Birhan, Amhara region, is a resource center educating over 600 students.

The World Bank has given $2.75 million to Burkina Faso’s Ministry of Economics and Finances for a project titled “Burkina Faso improving education for children with disabilities” to be implemented by the Ministry of Education and Literacy (MENAPLN). The project’s primary objective is to support the education of 7,000 vulnerable children with a focus on children with disabilities, including at least 50% of girls, in the five poorest regions of the country and Ouagadougou.

However, more effort and sustainable programs are needed to really make a difference when it comes to including children with disabilities in education in the three countries. Investing into data collection – both quantitative and qualitative – in order to understand where resources are needed most is important. In addition, policies aimed to change attitudes towards children and people with disabilities – such as educational or edutainment campaigns – might also rank high on the agenda. Training teachers and raising resources at the national and international levels could also help improve education for children with disabilities in the three countries.

Relevance for the Mauritian context

In Mauritius, the government is a signatory of all main conventions related to education and children with disabilities, and the constitution guarantees the right of all children to education. According to the most recent census (conducted in 2022), the proportion of children with disabilities in Mauritius is 2.3% of all children under 15. The figure increased from 1.5% in the 2011 census. As of October 2021, there were 2,754 students enrolled in the 72 special education schools in Mauritius, with the majority of the students being boys (67.4%).

Children with special needs are enrolled either in mainstream schools, special needs schools or integrated units within mainstream schools. However, important challenges include teachers’ lack of training in special education, lack of teaching aids and the lack of proper infrastructure, including teaching materials. The scope of the challenges is similar to those identified in the cases of Ethiopia, Burkina Faso and Niger, and in the case of Mauritius, these can be solved with appropriate resources and training. For instance, designating some schools as resource schools (as in the Ethiopia case), involving international organizations through knowledge exchange, or establishing partnerships between special needs educators in government and private schools, could be fruitful solutions for the future.

References

Hang’andu, P., Mensah, E.K., Nikolova, E. & Hayward, E. (2022). Educating Children with Disabilities. In: The Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Problems. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68127-2_238-1.

Includovate (2022). Study on the elements and economic costs of disability for children with disabilities and persons with physical disabilities in South Africa, Part 2. Report prepared for UNDP South Africa, March 2022

Main Photo by freepik on Freepik.

Charles Telfair Centre is an independent nonpartisan not for profit organisation and does not take specific positions. All views, positions, and conclusions expressed in our publications are solely those of the author(s).