Ifesinachi Okafor-Yarwood, Lecturer, University of St Andrews

Freedom C. Onuoha, Professor of Political Science, University of Nigeria

Les précieuses ressources océaniques de l’Afrique ont suscité l’intérêt des nations étrangères, en particulier celles de l’Occident et l’Asie.

La façon dont elles exploitent ces ressources peut être problématique car ces océans offrent un large éventail de ressources importantes – du poisson des minéraux et des hydrocarbures – qui sont également cruciales pour l’économie et la sécurité alimentaire du continent.

Mais dans certains pays, les intérêts étrangers dominent. Par exemple, les secteurs exploration pétrolière, transport maritime, infrastructure portuaire et pêche industrielle du continent sont parfois dominés par des entreprises étrangères.

La production pétrolière de l’Angola, par exemple, est dominée par les grandes sociétés internationales d’exploration et de production pétrolières, notamment Total (France) avec une part de marché de 41 %, Chevron (États-Unis) avec 26 %, Exxon Mobil (États-Unis) avec 19 % et BP (Royaume-Uni) avec 13 %.

Ainsi, bien que ces eaux soient vitales pour les pays africains et leurs citoyens, les acteurs étrangers agissent au mieux de leurs intérêts, parfois au détriment des pays et des citoyens africains.

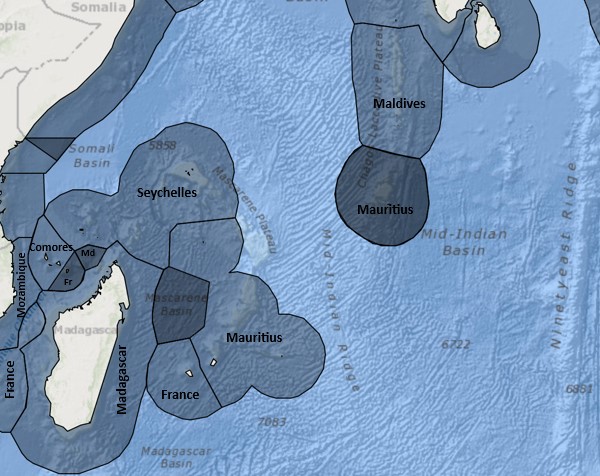

La sécurité maritime (océanique) en est une illustration. La Convention des Nations unies sur le droit de la mer (UNCLOS) stipule que les pays côtiers sont responsables de la gestion de la sécurité de leurs eaux territoriales (jusqu’à 12 milles nautiques de leurs côtes) et de leurs zones économiques exclusives, entre 12 et 200 milles nautiques de leurs côtes. Cela inclut la protection contre les actes illicites en mer, tels que la pêche illégale, la piraterie et les vols à main armée, le terrorisme et d’autres crimes connexes.

Cependant, la même convention permet à d’autres pays d’agir contre la piraterie, par exemple, dans les zones économiques exclusives.

En nous appuyant sur notre expertise en matière de gouvernance et de sécurité maritimes en Afrique, nous avons examiné la littérature, les bases de données de documents politiques et les rapports sur la sécurité maritime, afin d’explorer la manière dont les pays non africains définissent de manière sélective ce qui constitue des menaces. La façon dont ces menaces sont formulées détermine la réponse à y apporter et la façon dont cette réponse est financée. Cela a pour effet de saper une notion holistique de la sécurité maritime qui profiterait aux populations africaines.

Nous affirmons que les pays non africains se concentrent sur la piraterie et les vols à main armée en mer, qui menacent l’extraction des ressources, le transport et la sécurité. Ils ne s’intéressent guère à la protection des ressources marines de l’Afrique, en particulier contre la pollution et la pêche illégale causées par des puissances étrangères.

Cette approche est illogique. Elle ne tient pas compte du fait qu’il existe un lien entre la privation et les crimes maritimes, y compris la piraterie et les vols à main armée en mer. Les communautés côtières africaines, dont beaucoup sont déjà marginalisées et démunies, dépendent fortement des ressources marines. L’épuisement de ces ressources ne fait qu’aggraver leur situation. Si la protection des ressources marines africaines n’est pas considérée comme une priorité, les populations s’enfonceront encore plus dans la pauvreté et le cycle de l’insécurité en mer se poursuivra.

Lutte contre la piraterie

L’attention portée par les pays étrangers à la piraterie est évidente. Plus de 20 résolutions du Conseil de sécurité des Nations Unies ou déclarations présidentielles ont été publiées sur la piraterie dans le golfe d’Aden (Afrique de l’Est) et le golfe de Guinée (Afrique de l’Ouest et Afrique centrale).

La piraterie est un problème. Elle peut donner lieu à des enlèvements contre rançon et, dans des cas extrêmes, peut entraîner la mort de membres d’équipage. Entre 2005 et 2012, les pirates du golfe d’Aden ont reçu une rançon estimée à 500 millions de dollars. Près de 2 000 marins ont été enlevés et beaucoup ont été tués.

Au plus fort de la piraterie dans le golfe de Guinée, les pirates gagnaient environ 4 millions de dollars par an.

Les premières résolutions de l’ONU sur la piraterie en Afrique ont été introduites dans le golfe d’Aden en 2008 et dans le golfe de Guinée en 2011. Depuis lors, les incidents de piraterie ont diminué dans les deux golfs.

Les poissons et l’environnement

Mais le problème est que les nations africaines doivent se concentrer sur la protection des stocks de poissons et de l’environnement qui affecte les moyens de subsistance et les sources d’alimentation des citoyens africains. Certaines menaces – comme la pollution par les hydrocarbures et la pêche illégale – sont souvent le fait d’entités étrangères.

Le poisson est une source de nourriture et de revenus pour des millions d’Africains. Lorsqu’il y a moins de poissons, la pauvreté augmente, tout comme le nombre d’enfants non scolarisés et les problèmes de santé.

Pourtant, comme nous l’avons constaté au cours de nos recherches, il n’existe aucune résolution des Nations Unies concernant la dégradation de l’environnement ou le pillage des ressources marines. Ces phénomènes sont généralement causés par la pollution et la pêche illégale perpétrées par des entreprises étrangères et des navires hauturiers.

Un accord visant à mettre fin aux subventions préjudiciables à la pêche, qui favorisent la surpêche et la pêche illégale, a été adopté lors de la conférence ministérielle de l’Organisation mondiale du commerce en 2022. Mais à ce jour, seuls quatre pays ont adhéré à cet accord.

Avec la pollution, la surpêche et la pêche illégale sont des facteurs clés qui contribuent à l’épuisement des stocks de poissons en Afrique, plongeant les populations dans la pauvreté. En Afrique de l’Ouest, par exemple, les revenus des petits pêcheurs ont diminué de 40 % entre 2006 et 2016. La réduction des prises a également entraîné une diminution de la disponibilité et une augmentation des prix du poisson destiné à la consommation locale.

Pêche illégale

La pêche illégale, pratiquée en grande partie par des flottes étrangères, aggrave l’épuisement des stocks de poissons. Elle a un impact massif sur les économies. En Afrique de l’Ouest, elle coûte à six pays environ 2,3 milliards de dollars chaque année.

Malgré le succès de la coalition internationale en matière de neutralisation de la piraterie dans le golfe d’Aden, la pêche illégale par des navires étrangers continue de représenter une menace importante pour la sécurité alimentaire et économique de millions d’Africains.

Ce qui est ironique, c’est que la pêche illégale a été citée comme l’un des principaux facteurs contribuant à la piraterie dans le golfe d’Aden. Et dans le golfe de Guinée, la pollution historique causée par les compagnies pétrolières étrangères et les privations qui en résultent ont donné lieu à un militantisme qui s’est transformé en piraterie.

Il est concevable que plus les gens sont poussés vers la pauvreté, plus ils se lancent dans des activités criminelles dont la piraterie.

Changement d’orientation

Se concentrer principalement sur le piratage n’est pas la solution. Il faut s’attaquer à ses causes profondes – l’épuisement des stocks de poissons, la perte des moyens de subsistance et la pauvreté.

La sécurité maritime en Afrique ne sera assurée que lorsque les gouvernements africains et leurs homologues étrangers accorderont le même niveau d’attention et de ressources à la lutte contre la piraterie qu’à la pêche durable et à la lutte contre la pollution marine.

Pour parvenir à cet équilibre, il faut prendre plusieurs mesures concrètes.

5 mesures à prendre

Tout d’abord, l’Union africaine (UA) et les communautés économiques régionales doivent prendre des mesures collectives pour mettre fin aux relations d’exploitation des ressources océaniques du continent. Il s’agit notamment d’exhorter les Nations unies à reconnaître la pêche illégale et les crimes qui y sont associés comme des menaces graves pour la sécurité.

Les partenaires internationaux doivent aller au-delà de la rhétorique et cesser de financer l’exploitation des ressources du continent par le biais de subventions permettant l’exploitation légale d’espèces épuisées et de la pêche illégale.

Deuxièmement, les États africains doivent adopter une approche holistique de la sécurité maritime qui encourage la coopération et la collaboration entre les secteurs, comme le soulignent l’Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy AIMS 2050 et la Charte de Lomé. Cette approche devrait s’appuyer sur des mesures de lutte contre la piraterie pour combattre la pêche illégale et les activités connexes.

Troisièmement, pour comprendre l’impact des menaces qui pèsent sur la sécurité maritime et l’extraction des ressources, les voix africaines (au niveau communautaire) devraient être prises en compte dans la formulation des politiques et des stratégies.

Quatrièmement, bien qu’elle ait permis de réduire la piraterie, l’approche actuelle de la sécurité maritime en Afrique n’est pas durable. Il convient de s’attaquer aux causes profondes de l’insécurité, telles que le chômage des jeunes et la dégradation de l’environnement. Cela nécessite une attention immédiate qui met l’accent sur le bien-être social et écologique.

Enfin, la réduction des incidents de piraterie et de vols à main armée en mer, en particulier dans le Golfe de Guinée, est due à la coopération, la collaboration et la coordination entre les marines régionales et leurs partenaires. Il est largement admis que c’est une approche durable. Elle devrait être maintenue, voire étendue à d’autres menaces pour la sécurité en mer.

En prenant ces mesures, on s’assurera que personne n’est laissé pour compte et que les perspectives de prospérité future du continent ne sont pas compromises.![]()

Cet article est republié à partir de The Conversation sous licence Creative Commons. Lire l’article original.

Main photo by Francisco Davids on Pexels.

Charles Telfair Centre is an independent nonpartisan not for profit organisation and does not take specific positions. All views, positions, and conclusions expressed in our publications are solely those of the author(s).