Professor Lina Pelliccione, Pro-Vice Chancellor Curtin Mauritius, Professor Linley Lord, Pro-Vice Chancellor Curtin Singapore, and the Curtin University Risk & Assurance Team

In this paper, Lina Pelliccione and Linley Lord review how Curtin University’s values-led system and effective risk management structures across its national and international campuses have fed a culture of risk management, agility, care and communication. These have been instrumental in the university’s resilience and ability to adapt and successfully transition to fully online learning during the current pandemic. In light of Curtin’s success, the authors propose some guiding principles that may be helpful to other organisations in preparing for and surviving future crisis incidences.

Curtin’s values: Building on a foundation of integrity and respect, and through courage, we will achieve excellence and have an impact on the communities we serve.

What role do universities play in times of crises? What can we learn about resilience that will help individuals and organisations grow following this current global pandemic? Professor Deborah Terry, AO, Universities Australia Chair, Vice-Chancellor, Curtin University in her address at the Australian National Press Club Address, 26 February 2020 explained that:

Universities are some of the most adaptive, resilient, self-renewing institutions in human history. Our constant is change. Every so often, it’s predicted that universities may soon be under threat. Existential threat, no less. Yet what the doomsayers overlook is the restless instinct of universities for transformation and reinvention. These important institutions of society are not frozen in time. They are dynamic and ever-evolving. We’ve stood the test of time precisely because we’re adaptive. And we will continue to be so.

Curtin University is a leading global university with a mission to transform lives and communities through teaching, research and its industry and community relationships. It has campuses in Western Australia, Malaysia, Singapore, Dubai and Mauritius and is ranked in the top 1% of universities worldwide in the highly regarded Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) 2019.

Curtin University, like most education Institutions, has been impacted by COVID-19. This includes concern for the safety of staff and students in all their locations and financial losses resulting from the closing of borders to international students. Similarly, the sudden need to move everything online and to self-isolate has put significant pressure on university systems. Suddenly, the university community had to navigate new learning, teaching and research environments.

Values Led Learning Organisation

Curtin University is a values-based learning organisation, with proactive risk assessment and dynamic Prevention Preparedness Response and Recovery (PPRR) systems in place. There are sophisticated and mature communication protocols which help ensure people stay connected and have access to relevant information. These key elements have proven essential in such a complex global organisation spanning different countries, cultures and importantly, Government Authorities. This paper outlines these elements concluding with some key guiding principles that may be helpful to other organisations in preparing for and surviving future crisis incidences.

Curtin has a strong risk management culture which, coupled with a dynamic critical incident approach, has enabled the University to act swiftly to respond to COVID-19.

Risk Management Culture & Critical Incident Approach

Curtin University has a distributed leadership model (1). This has proven to be well suited to its global network of campuses, especially during these challenging times. Curtin also has a strong risk management culture which coupled with a dynamic critical incident approach has enabled the University to act swiftly to respond to COVID-19.

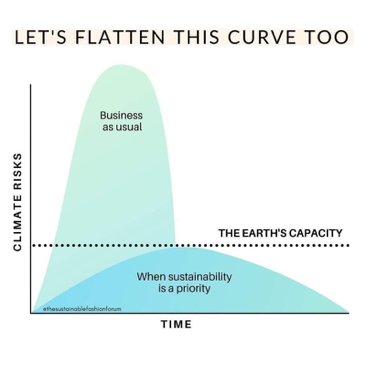

A strong risk culture is generally thought to be valuable to an institution as it is said to strengthen the institution’s resilience (Fritz-Morgenthal, Hellmuth & Packham, 2015, p 71).

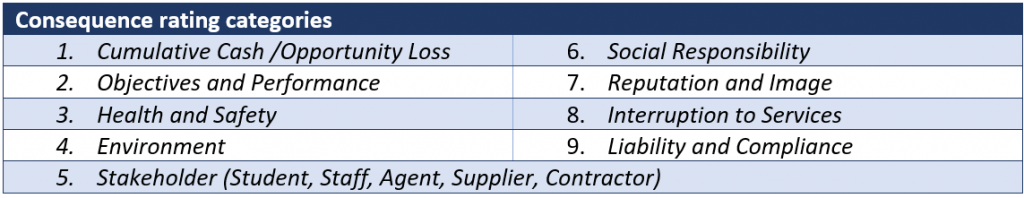

The Risk Reference Tables developed by Curtin are based on ISO 31000, the international standard for risk, guiding how risks are evaluated, assessed, measured, accepted and reported. As well as establishing a common language, the use of semi-quantitative measures removes some of the subjectivity of assessment processes and allows risks to be assessed across all Curtin’s locations.

Curtin uses five different rating tables: Controls; Consequence; Likelihood; Risk Matrix; and Risk Acceptance Criteria. The Consequence rating categories include key areas (listed below), which, if impacted would have a significant effect on Curtin’s ability to achieve its goals. Not surprisingly, the nine consequence categories have all been impacted by COVID-19.

Curtin Risk Reference Table – Consequence ratings categories

The regular use and monitoring of the risk framework as a benchmark has been essential for building a strong appropriately calibrated risk management culture. Adding to this is the confidence in and success of the Critical Incident Approach (PPRR) adopted by the University. These systems and protocols are embedded in the culture, enabling individuals to respond within an understood framework that recognises the particular context reflected in different campus locations.

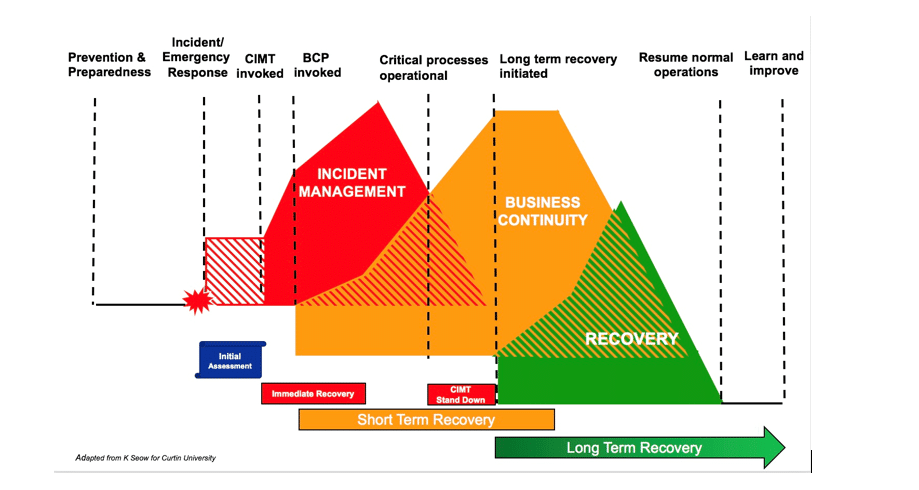

Outlined below are the key stages of the Critical Incident Approach adopted by Curtin. The focus is on the Australian context but the principles apply across all locations with global issues considered and managed by the Critical Incident Management Team (CIMT). The CIMT consists of University Executives, Directors and Managers, who together, provide stewardship in times of crisis. Members are selected based on the appropriate knowledge, skills, experience, authority and accountability to resolve the incident and facilitate a coordinated approach.

As a learning organisation, there is a culture of sharing, gathering and analysing information, together with regular reviewing and reporting.

Prevention and Preparedness – In line with the PPRR approach, the University has appropriate controls and processes in place. Key elements include the critical incident management framework, the alert matrix, emergency management plan, pandemic plan, and the CIMT structure. As a learning organisation, there is a culture of sharing, gathering and analysing information, together with regular reviewing and reporting.

The CIMT normally meets monthly where function leaders and alternates practise as a team. CIMT reviews and considers a range of emerging threats and implements outcomes from lessons learned to strengthen the CIMT framework. To strengthen its preparedness, the CIMT uses its external networks to form collaborations with State and National agencies, other universities, emergency providers, and subject matter experts.

The University’s Incident Alert Matrix is aligned with Risk Reference Tables providing clear understanding of the nature of incidents wherever they occur and the level to which these should be escalated. Ongoing disclosure of incidents is actively encouraged across areas in all locations and links to Curtin’s risk culture. Understanding the severity levels are critical to identifying and prioritising incidents against agreed levels of Yellow, Amber and Red. This helps avoid individuals applying their personal risk appetite and provides a shared view of Curtin’s risk appetite.

The PPRR Continuum below, illustrates the rhythm and flow of prevention actions, preparedness that instructs an Incident/Emergency response. The CIMT takes stewardship almost immediately after the incident has been assessed as critical. When critical processes are operational, the Business Response Team takes over to initiate long term recovery. Once normal operations resume, a key part is capturing lessons learned, resulting in corrective actions.

Prevention, Preparedness, Response and Recovery (PPRR) Continuum

Putting it into Action

Global framework encompassing local directives and initiatives

Curtin activated the CIMT and its Pandemic Plan on 23 January, after issuing travel safety guidance to staff and students the day before. On 28 February 2020, the World Health Organisation increased the global rating for the COVID-19 virus outbreak to ‘very high risk’ at a ‘global level’ triggering the Australian Government’s activation of its emergency response plan. The Curtin Pandemic Plan is overseen by the CIMT, led by the Chief Operating Officer. As well as implementing the University’s Pandemic Plan the CIMT were bound and guided by Government directives in all its locations. The common mantra advocated by the Vice-Chancellor was always to follow the Government directives of the specific location.

The Pandemic state highlighted some added complexities when dealing in a global arena with campuses around the world. In particular, how each of the local Governments responded to COVID-19 and how quickly each campus could transition staff and students to online learning.

Each campus was required to adapt quickly to their own context while working within a global framework. The framework had to be robust, yet agile enough to allow for differentiated actions. The Senior Executive received updates from the CIMT leader and campus Pro-Vice Chancellors at their weekly meetings. Thus, the experience and learnings from each context contributed to the overall management of the organisation and the well-being of Curtin’s global community.

The experience and learnings from each context contributed to the overall management of the organisation and the well-being of Curtin’s global community.

Values based leadership and risk culture facilitated agile and innovative actions

Additional initiatives supporting staff and students accessible by all campuses were established at the central level. In collaboration with each of our partners, global campuses provided additional support (setting up virtual community groups, IT help, mobilised administrative staff to support students and teaching staff, food packages etc.) to complement those at the central level. The University made special bursaries available to students in need and launched the Curtin Cares campaign to raise additional funds to further support students. Staff and students were also able to access well-being support during this crucial time. This demonstrated a key signature behaviour of the values based and led University; the health and safety of its people, including the wider community which were are at the heart of decisions and their first priority. The general consensus from students across all campuses is that they were satisfied with the way the University has been dealing with COVID-19.

Communication – effective and timely is essential

In this current crisis where our world has shrunk to our own home and in many cases, social isolation for a prolonged period of time, communication becomes a lifeline to the outside world. Importantly, there is always a key Communication specialist on the CIMT. They collaboratively developed a dedicated website for students, staff, and the wider Curtin Community. The Vice-Chancellor communicated very regularly via email and video with concise, relevant information. These messages were monitored carefully and contextualised for the appropriate global target audience instilling a high level of confidence in the University.

Final Comment – Key Principles

As a values-led, learning organisation, Curtin University is a place where behaviours and actions are guided by values and learning is deeply embedded in the culture. The organisation has developed a strong risk management culture and incident/crisis management demonstrating their commitment to the health and safety of people and the organisation. Their agile frameworks and distributed leadership model across campuses is a valuable blueprint for a global organisation needing to respond to constant change.

In summary, the following key principles have been important in guiding Curtin’s response and will continue to see the organisation through this crisis and what will follow:

- Values based leadership with a priority on health and safety

- A global unified plan that recognises the requirement for a local differentiated approach

- Building an effective risk management culture that informs agile and strategic decision making

- Effective targeted and timely communication

How has your organisation responded to the pandemic? Use the comment section to add other key learnings.

(1) See also Peter Senge (1990)’s seminal book, the Fifth Discipline, which introduced the concept of distributional leadership where organisational and individual learning are linked.

Charles Telfair Centre is an independent nonpartisan not for profit organisation and does not take specific positions. All views, positions, and conclusions expressed in our publications are solely those of the author(s).

La Banque Centrale de Maurice a mis en place la Mauritius Investment Corporation

La Banque Centrale de Maurice a mis en place la Mauritius Investment Corporation