Hippolyte Fofack, Chief Economist of the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank).

CAIRO – In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused Africa’s first recession in 25 years. The sharp tightening of global financial conditions triggered sudden stops in foreign direct investment and massive capital outflows, alongside one of the most dramatic global demand and supply shocks on record. The crisis intensified the continent’s liquidity constraints and compounded its existing macroeconomic management challenges.

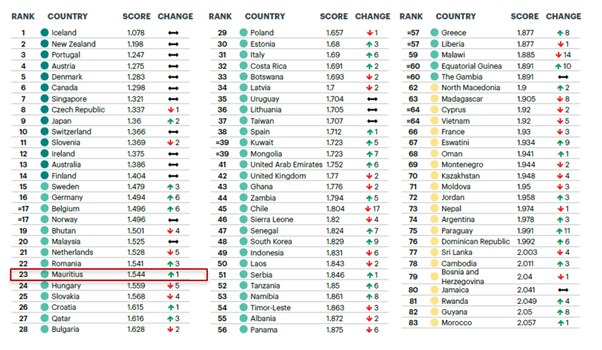

The pandemic-induced downturn has also amplified one of Africa’s biggest development challenges: the high cost of “perception premiums.” These premiums reflect the overinflated risks perennially assigned to Africa, irrespective of its improving macroeconomic fundamentals or the global economic environment.

Fortunately, international leaders are finally discussing the problem. At last October’s annual meetings of the International Monetary Fund, Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva remarked that the world needs “to concentrate on reducing the perceived and real risk for investing in Africa so we can see this huge availability of financing for the rest of the world trickle down into Africa.”

On May 18, French President Emmanuel Macron, who has called for “fairer financing rules for African economies,” will host an international summit on providing support to spur the region’s recovery. International coordination will be essential to equalize access to development financing and mitigate the risk of a divergent, two-speed global recovery, which threatens to exacerbate the income gap between Africa and other parts of the world.

Galvanized by strong economic performance in countries like Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Ivory Coast, Sub-Saharan Africa has consistently been one of the world’s fastest-growing regions over the last two decades. Underscoring their resilience, several African countries expanded their output even during the pandemic, and two – Ethiopia and Guinea – were among the world’s five fastest-growing economies last year.

Moreover, Africa’s advances transcend economics. As Georgieva has noted, “By improving policies and by strengthening institutions, countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have made fundamental progress.” Over the past two decades, she said, extreme poverty in the region has declined by one-third, life expectancy has increased by a fifth, and real per capita income growth has averaged about 50%.

But these successes appear to have had little to no impact on the dominant credit-rating agencies. They downgraded South Africa – which accounts for more than 20% of total intra-African trade and is the continent’s leading driver of cross-border investment – and several other African countries to “junk” status at the height of the pandemic last year. The downgrades extended the already long list of African sovereigns deemed to be highly risky and subject to default-driven borrowing rates.

Some of these assessments seem erroneous in light of many African economies’ encouraging performance. Ethiopia’s GDP, for example, has increased more than tenfold since the turn of the century. And, in contrast to many other economies, the pandemic downturn did not entirely derail Ethiopia’s long-run growth trajectory. But it remains a sub-investment-grade borrower.

With African governments’ borrowing costs so high, annual interest expenses have become one of their fastest-growing budgetary expenditures, in many cases exceeding health budgets. In Zambia, interest payments rose almost 13-fold within a decade, from around $63 million in 2010 to more than $804 million in 2019. Across Africa, annual interest payments more than tripled over the same period, from $8.1 billion to around $24.9 billion.

Although interest expenses fell in 2020 (by 36.6% for Zambia and 26.6% for the region as a whole), they are expected to increase again after the crisis. This will reflect faster pandemic-triggered growth of external liabilities, as well as the expiration of temporary relief measures extended to vulnerable countries under the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative and the IMF’s Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust.

In a 2015 study, researchers at the University of Michigan estimated that African sovereigns were paying an interest premium on their external borrowing of around 2.9%, or an extra $2.2 billion between 2006 and 2014. That figure has probably increased since then, especially in view of widening spreads and the avalanche of rating downgrades.

This premium is a major impediment to African economies’ fiscal and debt sustainability and structural transformation. Africa’s total external debt is significantly lower in both absolute and per capita terms than that owed by advanced economies. But its ratio of external debt-service payments to budget revenues is significantly higher, reflecting the prohibitively high cost of default-driven rates.

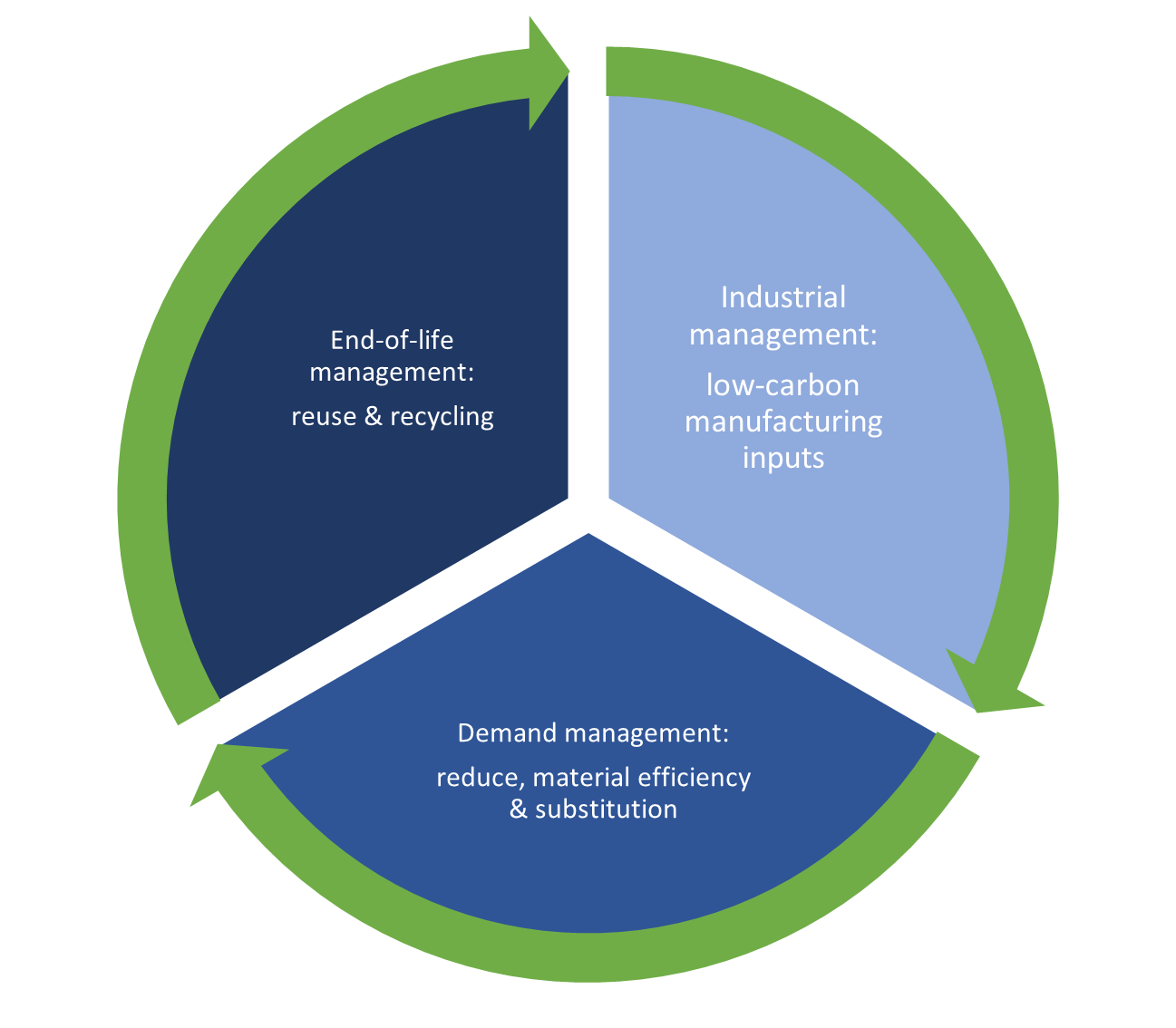

The region’s exposure to recurrent terms-of-trade shocks, which tend to increase trade and fiscal deficits and worsen liquidity constraints, has also amplified its high perception premiums. Structurally transforming African economies to diversify sources of growth and trade away from commodities will reduce this ancillary risk over time.

This will require, as Macron and Georgieva have stressed, large and sustained sums of patient capital to drive investment beyond natural resources. But default-driven borrowing costs and high perception premiums are, in all likelihood, the most acute obstacles on the path toward such structural transformation.

The international community responded rapidly to the pandemic, and introduced several initiatives to help low-income countries address acute liquidity constraints and mounting balance-of-payments pressures. In the short term, these measures will likely reduce eligible countries’ external debt-service payments and bolster their capacity to contend with COVID-19. But they do not address Africa’s fundamental development challenges.

Until global investors and major rating agencies accurately integrate Africa’s brightening realities and diverse circumstances into their models, many countries will remain on the verge of debt distress, and structural transformation that is key to fiscal and debt sustainability will remain elusive. We must therefore hope that Macron’s May 18 summit will help to reduce Africa’s damaging perception premium, and compel international investors and policymakers to give the region an equal opportunity to access global finance.

The Charles Telfair Centre is non-profit, independent and non-partisan, and takes no specific position. All opinions are those of the authors/contributors only.

This article was originally published by © Project Syndicate 2021 and is not under a Creative Commons Licence.

Main Photo by Pixabay/Unsplash