David Bach, Rio Tinto Chair in Stakeholder Engagement and Professor of Strategy and Political Economy, International Institute for Management Development (IMD)

Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s recent speech to the Communist Party Congress could be one of the most consequential of the decade. He told the audience – and the world – that his economic growth-crushing zero-COVID policy is here to stay, and that Beijing is more determined than ever to reunify with Taiwan, peacefully if possible and by force if necessary.

We are living in a moment of deep geopolitical rifts and extraordinary economic uncertainty, epitomised by Xi’s pronouncements. The world is clearly not reverting to some pre-COVID status quo. Instead, a combination of underlying forces has upended the previous world order and ushered in a period of profound disorder.

I want to look at four of these forces – the deterioration in US-China relations, Russia’s war in Ukraine, populism and inflation – to construct some political-economic scenarios for the next two to five years. Any list of destabilising global forces is necessarily incomplete. I won’t consider climate change or biodiversity loss (arguably the greatest challenges facing humanity), a possible COVID resurgence, the impact of artificial intelligence and other disruptive technologies, or the role of rogue regimes from Iran to North Korea.

Instead, I’m focusing on the areas that I believe will have the greatest impact on global business over the next several years – particularly because of their expected interaction.

1. Russia’s war in Ukraine

Not only did Russian troops fail to subdue Kyiv quickly as both the Kremlin and many western observers had assumed, Russia looks increasingly likely to lose the war – the mobilisation of reservists and nuclear sabre-rattling notwithstanding.

There are three reasons for this. First, the extraordinary poise and courage of the Ukrainian people, armed forces and leaders. Second, utter chaos on the Russian side. And third, the remarkable unity across the west that has provided Ukraine’s troops with sophisticated weapons, training and intelligence while slowly crippling Russia’s economy via boycotts and sanctions. Western businesses made important contributions as hundreds pulled out of Russia, stranding assets and foregoing profits.

Western unity faces its greatest test this winter if gas supplies in Europe run low and sky-high energy prices accelerate an expected slide into recession. Individual European governments may well waver over Ukraine if confronted by angry and cold voters.

Of course, Europe’s dependence on Russian gas is self-inflicted. As recently as 2014, only about 20% of EU gas was Russian. By early 2022, it was almost 40%. Despite loud warnings from Washington, Germany, the continent’s largest economy, actually increased its dependence after Putin’s illegal annexation of Crimea.

Berlin viewed Russian gas as cheaper and more sustainable than alternatives. Greater reliance also fitted a German foreign policy doctrine vis-a-vis the Soviet Union/Russia dating back five decades called wandel durch handel: change through trade. While dangerously naive in hindsight, a similar philosophy informed US policy toward China until recently, creating dependencies that are not vastly different.

2. US-China relations

For four decades following then US president Richard Nixon’s groundbreaking trip to China in 1972, the US sought better relations with Beijing via closer economic integration. Things began to change during Barack Obama’s second term, in response to Xi Jinping’s muscular posture at home and abroad, before subsequently rupturing with Donald Trump’s trade war.

If anything, the Biden administration has accelerated the switch from cooperation to confrontation via beefed up security alliances in the region with countries like Australia, export controls for advanced technologies such as microprocessors, and de facto defence commitments to Taiwan.

A day after Xi’s speech at the Party Congress, the US secretary of state, Antony Blinken, told an audience at Stanford University that in relation to strategically important Taiwan, Beijing was now “determined to pursue reunification on a much faster timeline” than previously.

Over the past several months, I have spoken with hundreds of mainly European senior executives about the current geopolitical panorama. Many described the difficult decision to withdraw from Russia. Yet, for most, Russia represents less than 5% of their business. When asked what they would do if the Taiwan situation escalates, the silence was deafening. With massive dependence on – and exposure to – both the American and Chinese markets, leaders from industries including automobiles and consumer and luxury goods readily admit they have no playbook.

3. Populism

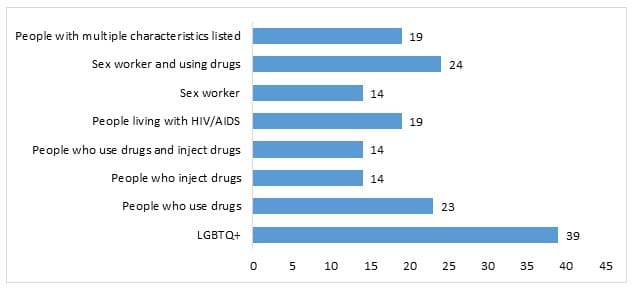

One reason why US policy toward Beijing is unlikely to soften is that China is one of few things the highly polarised US electorate agrees on. In 2011, only 36% of Americans viewed China unfavourably, with 51% having a favourable view. By 2022, a stunning 82% were unfavourable – a level only exceeded in Sweden, Japan and Australia.

Voters across western democracies also increasingly distrust globalisation. Fuelled by growing economic inequality, a majority across 28 leading economies told research firm Edelman in 2017 that “globalisation is taking us in the wrong direction”. Alarmingly, Edelman found in 2019 that only 18% of respondents across developed economies affirmed that “the system is working for me”, with 34% being unsure and 48% outright declaring the system is failing them.

Support for democracy has weakened in parallel, especially among the young. Political scientists Yascha Mounk and Roberto Stefan Foa, respectively of John Hopkins and Cambridge universities, found in 2017 that whereas 75% of Americans born in the 1930s agreed it is “essential to live in a democracy”, the figure was just 28% among millennials.

Similar trends can be observed in many other countries. This has helped into power populists from Hungary’s Viktor Orban and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro to Donald Trump and, most recently, Giorgia Meloni – Italy’s most right-wing leader since Mussolini. Note that Italy had the world’s second-highest dissatisfaction rates with democracy in a 2021 survey, topped only by Greece.

4. Inflation

This deep discontent with the prevailing political-economic order was before inflation reached levels not seen in four decades. By hiking benchmark interest rates in response, the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank accept they may trigger a recession. Most analysts now expect one on both sides of the Atlantic in 2023.

Meanwhile, China’s zero-COVID policy continues to weaken the world’s second-largest economy while its struggling property sector threatens to engulf the global financial system. Pierre Olivier Gourinchas, the IMF’s chief economist, did not mince words about the world economy at the organisation’s annual meeting in early October, warning that the “darkest hours” are still ahead and calling the outlook “very painful”.

But an even greater fear is stagflation – interest rate hikes that crush growth, send unemployment soaring and fail to meaningfully reduce inflation. The interaction of such economic dynamics with anti-establishment populism would surely be profoundly destabilising for an already shaky global order.

Four scenarios

Drawing on the forces described above, I have been urging business leaders from across sectors to contemplate four scenarios. Scenarios are not about predicting the future. They are about preparing for the future amidst uncertainty.

I locate the possibilities along two dimensions – one economic and one geopolitical. On the economic dimension, the best case is that central banks and policymakers quickly bring inflation under control, recessions in major markets are short lived, and a global economic recovery begins in the second half of 2023 and accelerates in 2024. At the other extreme, aggressive interest rate hikes might surface and exacerbate structural weaknesses in the global economy, leading to a period of prolonged stagflation.

Similarly with geopolitics, Vladimir Putin might discover a face-saving retreat from Ukraine while Xi, with his third term secured, could dial back his rhetoric regarding Taiwan. Or more pessimistically, Ukraine could worsen sharply, for example, if Putin chooses to use tactical nuclear weapons or Nato is directly drawn into the conflict. Meanwhile, nationalist fervour might lead Xi to issue Taiwan an ultimatum, or an accidental use of force by either side could trigger a broader conflict.

By combining these different possibilities, I create my four scenarios. For illustrative purpose, I associate each with a decade of the 20th century – not because history will repeat itself, but to crystallise what is at stake and how much the possible futures differ.

When the pandemic’s end seemed in sight, several observers predicted a return of the “roaring twenties”. The original roaring twenties occurred after the first world war when the League of Nations ushered in a short period of international cooperation, global trade resumed and economies recovered. A latter-day equivalent certainly remains possible if global tensions ease and the economy recovers quickly.

Alternatively, we can imagine an economic recovery without easing global tensions. The early 1980s come to mind, when decisive action by the chairman of the US Federal Reserve, Paul Volcker, reduced inflation and after a short recession, growth resumed and the stock market boomed. Internationally, however, things were less rosy. The US-Soviet 1970s detente came to an end with respective boycotts of the 1980 and 1984 Olympics, a proxy war in Afghanistan and a renewed nuclear arms race.

The 1970s are my third scenario. They are frequently invoked as the exemplar of stagflation, with soaring prices, stubbornly high unemployment and plenty of labour strife. However, global tensions had eased, at least between the superpowers. The Spy Who Loved Me captured the zeitgeist as James Bond teamed up with a Soviet agent to save the world.

Compare this to the 1930s, another decade in the 20th century characterised by high unemployment, low growth and economic turmoil. Fascism swept away nascent democracies, global tensions escalated and the world experienced a catastrophe that remains singular in human history.

The world today is very different from the decades in these scenarios. Technology has ushered in unprecedented connectedness, stakeholders have become far more powerful, and global supply chains and financial systems have vastly increased economic interdependence. One hopes the horrors of the 20th century combined with the unimaginable destructiveness of modern weaponry limit potential conflict escalation.

Yet the contrast between the decades highlights how changes in just two variables might distinguish a scenario that is great from one that is good, one that is bad, and one that is truly terrible. Asking which is the most likely is the wrong question. It is more important for business leaders, governments and individuals to recognise that the previous world order is gone.

The most resilient organisations will be the ones that make decisions on the basis of a clear sense of purpose and strong values, not rigid strategies or action plans. Globalisation will not suddenly end, but firms will increasingly make decisions that go beyond looking for the cheapest supplier or the biggest new market.

The next few years are probably also not the best time for businesses to strive for maximum efficiency. Cash will be king, slack good and flexibility vital. Also, it will be critical for business leaders to proactively convey what they stand for – ideally before they get asked about the future of their China business, how they might handle labour unrest, or whether they believe in free and fair elections.

This period of disorder could be short or long, and the impact on organisations and societies could range from minor to dramatic, with considerable variation across industries and regions. Zeroing in on the underlying dynamics and contemplating their potential impact on business, government and society is something we should all do to effectively navigate the rapids ahead. ![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Main Photo by Tomas Ryant on Pexels.

Charles Telfair Centre is an independent nonpartisan not for profit organisation and does not take specific positions. All views, positions, and conclusions expressed in our publications are solely those of the author(s).