Professor Dale Pinto, PhD (Law) (Melb), MTax (Hons) (Syd), Chair of the Academic Board, Curtin University and Professor of Taxation Law, Curtin Law School, Curtin University

Academic boards represent a fundamental governance mechanism in the overall governance architecture of universities. This article examines the role and importance of academic boards in Australian universities. The article also makes observations about the future and continuing relevance of academic boards as part of the governance framework of Australian universities. Though the examination in this article is undertaken in the context of Australian universities, most of the commentary would be relevant to other higher education institutions, including those in the Indian Ocean region, as academic boards within universities generally exhibit common characteristics.

Introduction

In a 2007 thematic analysis of the role of academic boards in university governance, Dooley observed that:

Universities have evolved from medieval communities of scholars, through the ivory towers of the Oxbridge of yesteryear to today’s large-scale business model. The tension between their traditional character, where reasoned argument holds sway and issues are debated thoroughly until there is scholarly consensus, and the modern imperatives of efficiency and accountability for the bottom line of the budget are palpable in most modern campuses[1].

Dooley then argued that nowhere is this tension more keenly felt than at the level of the university academic board, variously referred to as the ‘academic senate’, ‘senate’ or ‘academic council’. This body will be referred to in this article as the ‘academic board’ or ‘the board’ which represents the peak academic governance body in Australian universities.

All Australian universities have a form of academic board, which is usually enshrined and created by or pursuant to an Act of Parliament that establishes the university itself. For example, Swinburne University in Victoria is established by the Swinburne University of Technology Act 2010 (Vic), and section 20 mandates that the Council must establish an academic board. My university – Curtin University – is established under the Curtin University Act 1966 (WA) and the academic board is established under Statute 21 which was created by the University Council under the powers conferred on it to make statutes by section 34 of the Curtin University Act 1966.

This legislative underpinning demonstrates the significance of academic boards in Australian Universities. However, despite academic governance being a crucial matter for all Australian universities, discussion of the role of academic boards is not widespread, as Baird observed:

Even though universities are heavily dependent on academic boards for quality assurance in the core areas of teaching and research—on paper, at least—discussion of the roles of academic boards is not widespread[2].

In addition to the significance of this legislative underpinning, it is both timely and relevant to examine the role and importance of academic boards in the governance framework of Australian universities as academic boards are central to the regulatory regime which governs universities. In Australia, this is overseen by the Tertiary Education and Quality Standards Agency (TEQSA)[3]. Other recent examples, including the Walker review which examined the role of academic boards in promoting freedom of speech and academic freedom,[4] demonstrate the timeliness of examining the role of such boards to ascertain if they are functioning as intended.

Role of Academic Boards

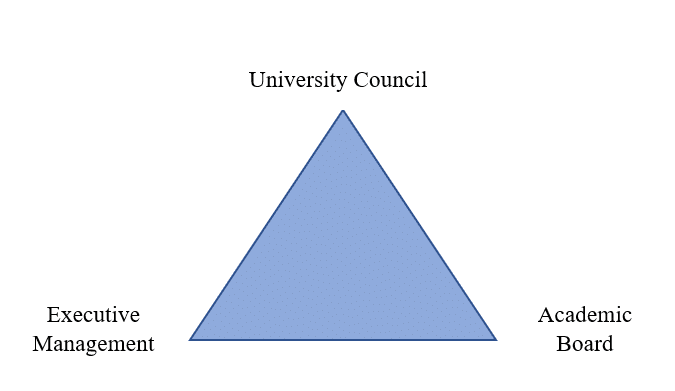

Traditionally, a tripartite governance structure operates at Australian universities in which the executive management of the university (led by the Vice-Chancellor) and the academic board contribute to academic decision-making within the context of the university council’s overall responsibility as the peak governance body in a university.

This is neatly depicted in the ‘governance triangle’ below, which derives from models presented by Clark (1983),[5] Dooley (2006)[6] and Shattock (2012)[7].

The governance of a university operating under this model involves:

- Corporate governance: ultimately rests with council as the peak governance body. Council is assisted by its committees (of which an academic board is typically one such committee) in the effective discharge of its responsibilities.

- Academic governance: academic boards typically function as the principal policy-making and advisory body on all academic matters pertaining to and affecting a university’s teaching and research. As such, an academic board is responsible for assuring academic standards and quality, and, in fulfilling this function, ensures academic integrity and high standards in teaching, research, assessment, and admissions[8]. It carries out these functions in partnership with, but independently of, the Vice-Chancellor’s executive management team referred to in the figure above as the ‘Executive Management’.

- Executive management: Led by the Vice-Chancellor who allocates roles and responsibilities to university management. The Vice-Chancellor typically has several advisory committees to provide advice and assurance in decision making and to assist in meeting the requirements of external bodies including regulators.

An academic board is formally constituted and has a clearly defined role, normally enshrined in its Terms of Reference or Constitution which will specify, among other things, its functions and powers, membership, meeting protocols, powers to establish committees, review processes and reporting requirements.

University academic boards are presided over by a Chair, who is normally elected and supported by a Deputy, again normally an elected role. It is desirable, and almost universal, that the Chair is an ex officio member of the university council. Frequent and full communication between the Chair, Deputy Chair, Secretariat which supports the board, the Vice-Chancellor and council is essential for the effective functioning of the university governance structure as described above.

Importance of Academic Boards: three key functions[9]

Maintenance of Academic Standards

The board and its standing committees shoulder an important responsibility for ensuring the quality and integrity of all academic endeavours is maintained, including learning and teaching, and research. The board has an established, accountable, and transparent framework for the implementation and review of policies as they relate to academic activities; for the development and review of academic quality assurance measures; for facilitating compliance with its policies and procedures; and for monitoring and ensuring remedial action is taken when it finds non-compliance.

The board has delegated authority from the university council for approval, accreditation[10] and review of new and existing academic programs, including those offered by commercial entities owned or partially owned by the university and those offered in partnership with other institutions. The board has the responsibility and authority to determine compliance of academic programs with the Higher Education Standards Framework (Threshold Standards) 2015 (HESF) [11] which represents the basis for the regulation of higher education providers and courses by the regulator, the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA). The board also must ensure compliance with individual institutional qualifications standards.

In short, the board has the responsibility for the ultimate academic oversight of all academic programs, onshore and offshore, and its approving and monitoring functions play a key role in ensuring comparability of standards, both internally and externally, and in the maintenance of standards in academic partnerships.

In terms of learning and teaching, the board has an important role in the assessment and evaluation of learning and teaching and in ensuring the quality of, and improvement in, teaching and learning practices as well as in approving new courses. It also plays a key role in overseeing student experience and retention.

The board also has an important role in approving research policies, and in encouraging and supporting research.

Finally, academic boards themselves undergo periodic independent external reviews at least every seven years to align with the HESF in relation to Governance and Accountability (Standard 6.1 3(d)). These reviews are important as they assess the effectiveness of the board and the academic governance processes of the university. Curtin most recently undertook such a review in 2018 and it resulted in a newly configured committee structure, changes in committee composition (e.g., to include more student representation) and a sharper definition of the role of the standing committees to better align their role to the board and to achieve a clearer line of sight to both faculties and Curtin’s global campuses.

Involving and communicating with Internal Stakeholders

As academic boards bring a whole of institution perspective to academic matters, it is important that it seeks wide input (including through its standing committees) before it makes decisions and communicates its decisions to maximise efficiency and quality and remove unnecessary duplication. Key stakeholders in this process include faculties, global campuses and council and it is important that academic boards maintain a clear line of sight to all these stakeholders.

Key communication channels for academic boards can be classified as vertical – between the Council, academic board, and broader academic community, and horizontal – between the academic board, faculties, global campuses and other academic units and support units. The Chair of the academic board, along with the Secretariat which supports the academic board, both play a key role in maintaining effective vertical and the horizontal communications.

Key mechanisms to ensure effective communication include: timely preparation and distribution of agendas, meeting papers and minutes; summary reports of main outcomes – e.g., at Curtin the Chair and Secretariat prepare a high level summary of outcomes for communication across the university and to council; professional, respectful and robust meetings conducted in accordance with the university’s values; and clear and accessible information which should be available via a secure board portal for all members of the academic board.

The academic board ensures that its committee structure supports open and transparent communications within the institution and plays a key role in coordination and oversight of its committees.

Finally, the university’s staff induction processes educate staff about the academic board’s role within the university and is an important activity for members joining the board for the first time, particularly to assist some members (e.g. students).

Accountability to External Stakeholders

In addition to ensuring effective involvement of and liaison with internal stakeholders, academic boards have responsibilities to many external stakeholders.

First, academic boards have a central role in setting and monitoring university admission and policies to ensure standards, equity, and diversity.

Second, academic boards have oversight of academic policies that regulate academic credit transfer and articulation arrangements. Academic boards also need to have appropriate structures and quality assurance processes to foster and ensure high standards in community-engaged learning activities.

The board provides substantial input for external audits by TEQSA, and it is often involved with accreditation processes of external professional accrediting bodies.

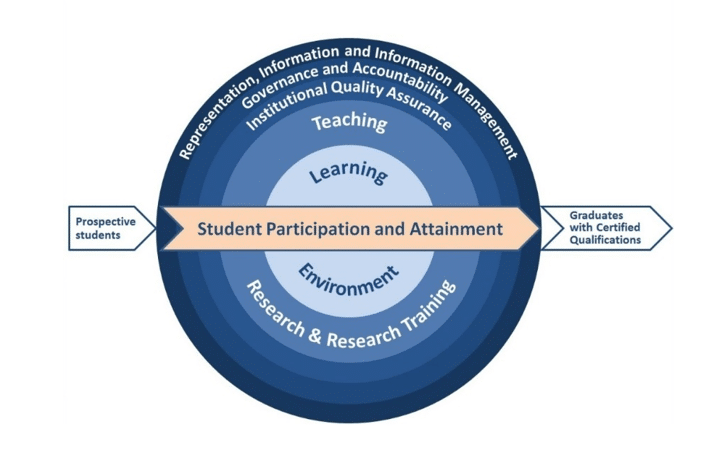

TEQSA sees ‘academic leadership’ in higher education providers as a subset of the overall institutional or corporate leadership of the provider, differentiated mainly by its focus on ‘academic matters’ (including teaching, research and related matters). It sees academic leadership as ‘the system of interdependent elements that together allow a provider to achieve (or at least support) and monitor its intended academic outcomes[12].’

The importance of academic leadership is reflected in its prominence throughout the HESF. TEQSA expects the provider to demonstrate that overarching leadership mechanisms are in place at the institutional level (corporate governance, academic governance, and quality assurance) to provide academic oversight and monitoring at that level, as required under the HESF.

As illustrated in Figure 2 below from TEQSA’s Guidance Note on Academic Leadership, the HESF aligns with the student experience or ‘student life cycle’[13]. The HESF is also grounded in the core characteristics of the provision of higher education and therefore, the Standards are intended to provide higher education providers with a framework for internal monitoring of the quality of their higher education activities which academic boards are responsible for overseeing[14].

More specifically, academic boards must oversee the two parts of the HESF:

Part A: Which prescribe standards for Higher Education. These standards represent the minimum acceptable requirements for the provision of higher education in or from Australia, and

Part B: Which sets out the criteria for Higher Education Providers. These criteria enable categorisation of different types of providers and whether a provider is responsible for self-accreditation of a course(s) of study it delivers.

These are significant responsibilities for universities to comply with and the role of academic boards in ensuring compliance with the HESF is therefore very important.

Constructive Confrontation [15]

In concluding, not everyone will agree with Professor Dooley’s view that academic boards should be the ‘engine room of the university’[16] but it can be seen from this brief article how important academic boards are in the overall governance architecture of Australian universities.

Perhaps as Shattock advocates, the focus should not be so much about effective governing bodies but more about effectively governed universities[17]. As he notes, universities remain ‘communities of scholars’ and will not be able to chart a future satisfactorily unless they encourage and nurture those communities to contribute to institutional decision-making. As part of that process the voice of the academic community, which is strongly represented via academic boards, must be a critical element of an effectively governed institution.

Robust, professional, and values-driven conversations should be encouraged within a governing body – referred to as ‘constructive confrontation’ by Shattock[18]– which is necessary and should be encouraged to produce well-reasoned and debated outcomes.

From my own experience, academic boards do engage in robust but professional and respectful debate on significant issues. Recent examples at my university include strong debates on changes to the academic calendar, changing the university graduate attributes and policies relating to freedom of speech and academic freedom. All of these issues involved a series of consultations and discussions with students, the academic staff association (staff union) as well as academics across not only our Perth-based campuses but also soliciting views from our global campuses. These consultations were effective in refining proposals put to the board by management by hearing the voices of the academic community and also the student voice which is greatly valued as part of the academic board’s deliberations at my university.

On this basis, academic boards should continue to assert themselves to balance all voices in a university community and provide sound academic advice to executive management and university councils as part of the well-accepted tripartite governance model referred to at the start of this article.

Main photo by Kookyrabbit

Charles Telfair Centre is an independent nonpartisan not for profit organisation and does not take specific positions. All views, positions, and conclusions expressed in our publications are solely those of the author(s).

_________________________

[1] Anthony H Dooley, The Role of Academic Boards in University Governance (AUQA occasional publications, No 12) 7.Charles Telfair Centre is an independent nonpartisan not for profit organisation and does not take specific positions. All views, positions, and conclusions expressed in our publications are solely those of the author(s).

[2] J Baird, ‘Taking it on board: quality audit findings for higher education governance’, Higher Education Research & Development (2007) Vol 26, No 1, 101–15.

[3] Though the analysis in this article is undertaken in the context of Australian universities, most of the commentary would be relevant to other jurisdictions as academic boards within universities generally exhibit common characteristics.

[4] Sally Walker, Review of the Adoption of the Mode Code on Freedom of Speech and Academic Freedom, December 2020.

[5] B R Clark, The Higher Education System (Berkley, California University Press), 1983.

[6] Dooley, above n 1.

[7] M Shattock, ‘University governance: An issue for our time’, Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education (2012), DOI:10.1080/13603108.2011.645082.

[8] See, eg, University of Queensland Academic Board Policy, paragraph 2.1 (c) (i) and (ii), available at <https://ppl.app.uq.edu.au/content/1.30.03-academic-board> (accessed 30 June 2021).

[9] A comprehensive explanation of these aspects is contained in the following paper presented at the National Conference of Chairs of Academic Boards/Senates in November 2013: ‘The Purpose and Function of Academic Boards and Senates in Australian Universities’. What follows on this point is based on this source.

[10] Accreditation in this context refers the responsibilities universities have as self-accrediting institutions to ensure the learning outcomes of qualifications meet internal and external standards. Professional accreditation bodies also play a role in ensuring learning outcomes meet the needs for specific professions – eg CPA Australia and CA ANZ have their own accreditation requirements for accounting courses which are offered by universities.

[11] The Commonwealth Minister for Education and Training promulgated new national standards for higher education in Australia – the Higher Education Standards Framework (Threshold Standards) 2015 (HESF). The HESF took effect from 1 January 2017. From this date, all providers of higher education in or from Australia must meet and continue to meet the requirements of the HESF.

[12] TEQSA, Guidance Note: Academic Leadership (18 June 2019), 1-2.

[13] TEQSA, Higher Education Standards Framework (Threshold Standards) 2015 – TEQSA Contextual Overview, Version 1.1, effective from 1 January 2017, 6.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Shattock, above n 6, 61

[16] Dooley, above n 1, 5.

[17] Shattock, above n 6, 61. What follows here draws from this source.

[18] Ibid.