Henri Casella, Senior Environmental Economist Consultant

Jaime de Melo, Professor Emeritus, University of Geneva

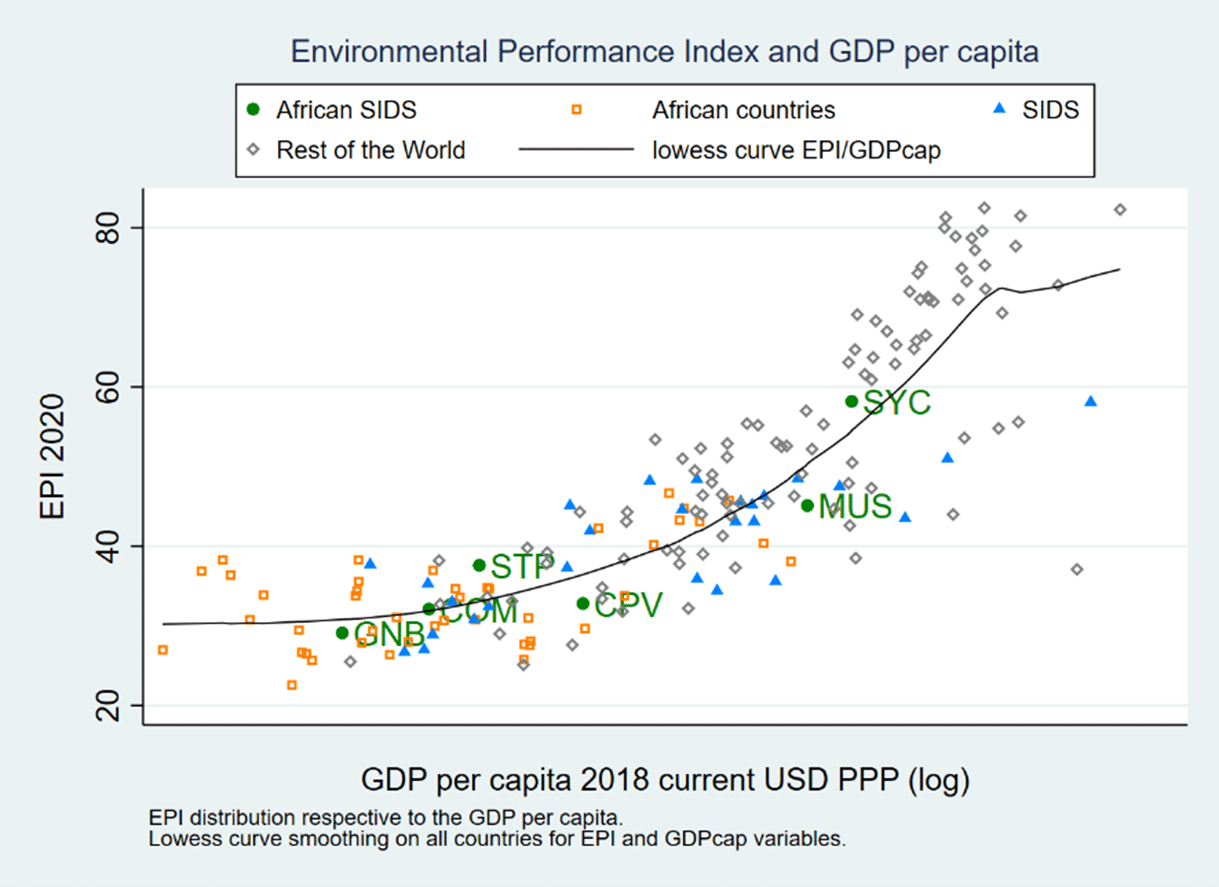

Usually, countries take better care of their environment as they become richer, both because citizens put greater weight on environmental quality and because governments have more resources at their disposal. For Mauritius, economic appraisals have often touted a “Mauritian miracle” by its high growth rates as reflected by the standard United Nations System of National Accounts (SNA) that ignores depreciation of natural capital. Yet for Mauritius, GDP growth was not accompanied by improvements of environmental indicators.

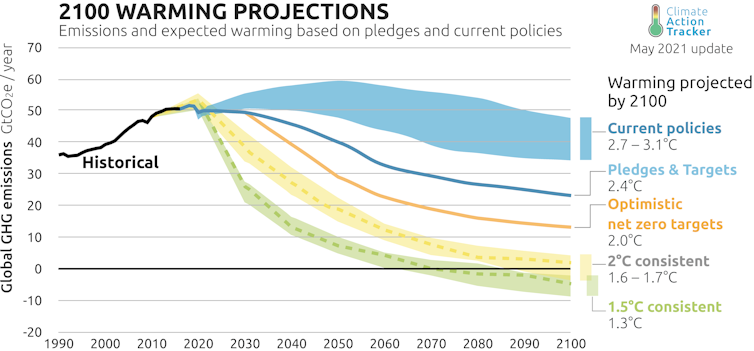

Indeed, Mauritius has fallen short of two important targets set on the global stage by Multinational Environmental Agreements (MEA). First, the country has missed the pledges made during Aichi Convention on Biological Diversity by a long shot[1]. On the Millenium Development Goals (MDGs) targets for CO2 emissions, the per capita emissions for 2015 was already off-track in 2010, continuing to grow every year, reaching 5.3Tco2e per capita in 2018 – 38% above the 2030 target[2].

Mauritius’ overall lacklustre environmental performance at its per capita income level is evident in its below-average position in an Environmental Performance Index (EPI) where all African Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are singled out. Seychelles and Saõ Tomé are ‘first in class’ while Cabo Verde and Mauritius are below the average fit (though in the top third among all SIDS).

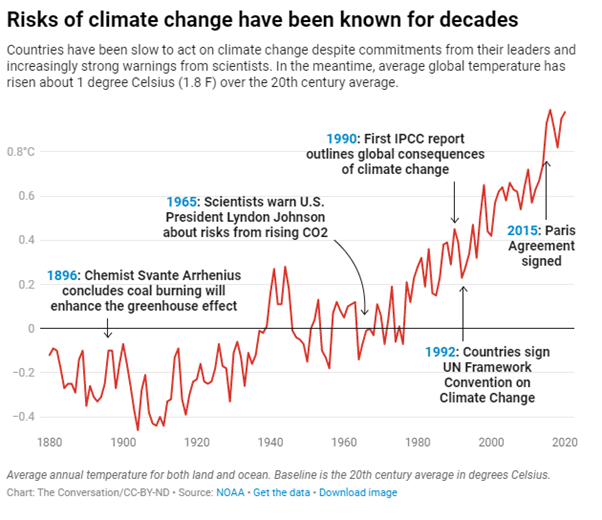

At the November 2021 COP26 assembly, Mauritius’ Prime minister laid out an ambitious plan for 2030, pledging a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions of 40% as well as a green energy push (60% of energy from renewables) while phasing out coal electricity. The pledge also included other commitments like protecting the island’s environment by moving towards a circular economy. [3]

It is widely accepted that the health of the environment and its ecosystems is particularly fragile in SIDS because of population pressures, biodiversity loss, and climate-change related pressures to which they are more vulnerable[4]. SIDS also depend strongly on international trade. If not accompanied by policies that protect their environment, as already noted by Pierre Poivre for the ongoing deforestation in Mauritius, international trade is likely to contribute to the degradation of their terrestrial and marine environments[5]. This note takes stock of Mauritius’ environmental performance by comparing it to that of three other African SIDS: Seychelles, Cabo Verde and Saõ Tomé drawing on a recent study comparing environmental performance across the four African SIDS[6].

Lessons from an environmental dashboard for SIDS

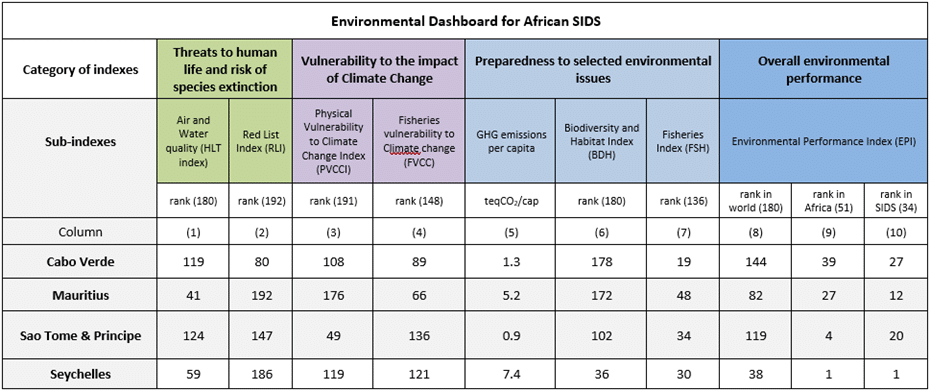

An environmental dashboard with indices covering three dimensions helps focus on SIDS environment-related characteristics and performance:

- The first considers the health of the environment with two indices that capture the level of pollutants in the air and water and the health of the ecosystem’s biodiversity[7].

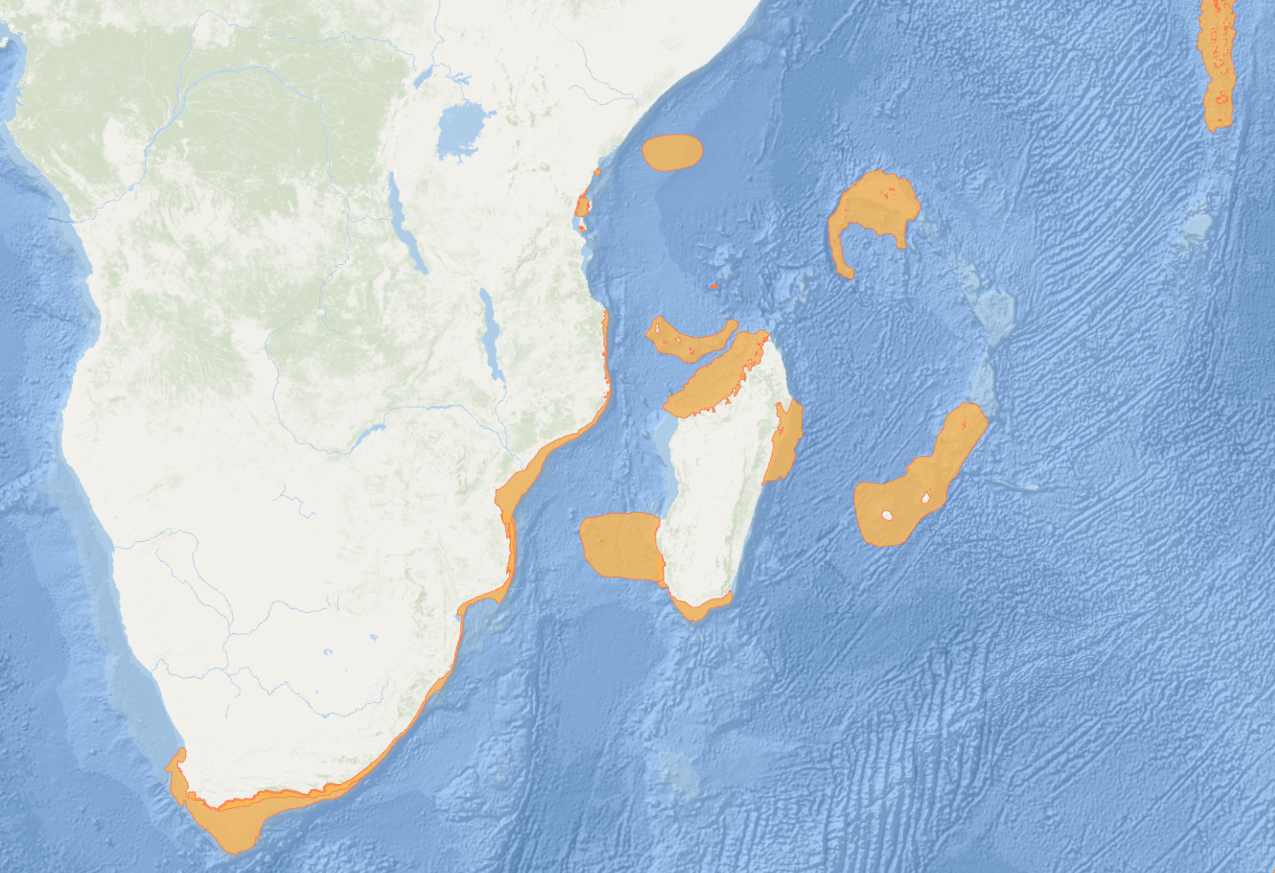

- The second captures vulnerability to environment-related shocks, first and foremost to the global climate change. Two vulnerability indices are selected: a Physical Vulnerability to Climate Change Index (PVCCI) (increase in aridity, sea level rising, higher occurrence of extreme events such as heavy rainfall, heatwaves and storms) and and an index to fisheries vulnerability to climate change (FVCCI).

- The third, Preparedness, is an outcome that captures policy measures taken to confront the selected environmental challenges: climate change, biodiversity loss and sustainable management of fisheries.

Diving into the specifics of the EPI score in columns 8-10 (Environmental Dashboard for African SIDS) shows a high vulnerability of Mauritius to climate change impact and high risks for the fisheries of Saõ Tomé and Principe and Seychelles. The risk of extinction of native species is also relatively high for both Islands. Mauritius ranks well when it comes to air and water pollutants, while Cabo Verde has a better rank on the species extinction index. Except for Mauritius, the other listed African SIDS have relatively good scores on fisheries management.

Next steps

If composite indexes like the EPI are only approximately informative of a country’s sustainability path, countries taking seriously their transition towards green growth should at least commit to produce reviews of annually updated (and easily available) environmental indicators like those, in a suitably designed environmental dashboard. The dashboard here designed for SIDS, provides indices countries can use to evaluate where they stand in the group, steering away from vague statements on the sustainability of their development paths [8]. The results could then be confronted with targeted policies to be reviewed and debated in national assemblies. Two examples illustrate steps to accelerate transition towards green growth.

For Seychelles, Laing (2020) proposes a blue economy valuation toolkit to modify the current system of national accounts to recognise the contribution of the blue economy to the sustainability of Seychelles’s development. The toolkit is to help towards a more accurate reporting of natural capital (e.g. artisanal fishery) while participation in the debt for nature initiative has led to designating 30% of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) as marine protected area following a comprehensive EEZ-wide marine spatial plan.

For Mauritius, joining the Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability (ACCTS) launched in September 2019 would have been an opportunity to make commitments on removing barriers to trade on Environmental Services, establish concrete commitments to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies and develop voluntary guidelines for eco-labelling programmes. For Mauritius, Parry (2012) estimated that applying corrective taxes on energy prices to correct damages from energy prices that do not reflect environmental damages would increase the Mauritian government revenue by 0.8% of GDP while reducing energy-related CO2 emissions by 9.7%.

Such difficult-to-take political measures would have been easier to sell in the context of small-group negotiations with other countries.[9]

Main photo by Colin Frankland on Flickr

Charles Telfair Centre is an independent nonpartisan not for profit organisation and does not take specific positions. All views, positions, and conclusions expressed in our publications are solely those of the author(s).

[1] Mauritius pledged to protect 17% of terrestrial and inland water as well as 10% of coastal habitat (Target 11) by 2025. As of now, only 4.725 % terrestrial area and 0.003% of marine and coastal area are protected (Voluntary national review report of Mauritius on SDG, 2019, Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

[2] Per capita GHG emissions in Mauritius are comparable with France and Mexico. Mauritius has pledged on several occasion to reduce GHG emissions compared to a Business as usual trend of 6.9MtCO2e per year in 2030 and most recently by 40% at COP26.

[3] High level statement at the COP26 in Glasgow. https://unfccc.int/documents

[4] See Nurse et al (2014) for the expected effects of climate change on SIDS. Nurse, L.A., McLean, R.F., Agard, J., Briguglio, L.P., Duvat-Magnan, V., Pelesikoti, N., et al., 2014. Small Islands. In: Barros, V.R., Field, C.B., Dokken, D.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Mach, K.J., Bilir, M. (Eds.), Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp.1613–1654.

[5] See Techera, E. (2021) “Deforestation, climate change and the emergence of legal responses: the international influence of Pierre Poivre’s environmental leadership”, forthcoming, Royal Society for Arts & Sciences of Mauritius/Académie des Sciences et des Belles Lettres of Lyon

[6] Low-income Comoros and Guinea Bissau have less policy space to take care of their environments so they are omitted from this article’s dashboard.

[7] Measured by the number of deaths and sick people due to air and water pollution and the number of species that are nearing extinction

[8] In its executive summary, UNEP (2015) p.1 states “Mauritius has been a beacon for other SIDS in terms of sustainable development. In the last decade, Mauritius has been investing in renewable energy, clean waste management technologies and in public transport technologies”. In Mauritius’ first voluntary national report on SDGs 0f 2019, the annex on the progress tracker states that for the environment -related SDGs( take urgen action against climate change (13), conserve and sustainably use the oceans (14), and preserve ecoystems (15), Mauritus was on track for 22 targets and had met 2 targets.

[9] Melo (2020) evaluates the prospects of the ACCTS to help put SIDS on track to adapt to climate change.

References

Blasiak, R., Spijkers, J., Tokunaga, K., Pittman, J., Yagi, N., & Österblom, H. (2017). Climate change and marine fisheries: Least developed countries top global index of vulnerability. PLoS One, 12(6), e0179632.

Casella, H. and J. de Melo 2021.Greening trade policies in African Small Islands Developing States (AFSIDS): suggestions for the Way Forward under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), https://ferdi.fr/en/publications/greening-trade-policies-in-african-small-islands-developing-states-afsids-suggestions-for-the-way-forward-under-the-african-continental-free-trade-area-afcfta

Feindouno S., Guillaumont P., Simonet C. (2020) “The Physical Vulnerability to Climate Change Index: An Index to Be Used for International Policy”, Ecological Economics, vol. 176, October 2020.

Government of Mauritius (2011) Mauritius Environment Outlook, 2011.

IUCN 2020. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2020-3. https://www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on [02/02/2021]

Laing, S. (2020) “Testing of a blue economy Valuation toolkit”, https://www.covid19platform.tradeeconomics.com/post/testing-of-a-blue-economy-valuation-toolkit

Melo, J. de (2020) “Negotiations for an Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability (ACCTS): An Opportunity for Collective Actions”, https://www.tradeeconomics.com/iec_publication/trade-climate-change-negotiations-action/

Nurse, L.A., McLean, R.F., Agard, J., Briguglio, L.P., Duvat-Magnan, V., Pelesikoti, N., et al., 2014. Small Islands. In: Barros, V.R., Field, C.B., Dokken, D.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Mach, K.J., Bilir, M. (Eds.), Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp.1613–1654.

Parry. I. W. (2012) “). Reforming the tax system to promote environmental objectives: An application to Mauritius”. Ecological Economics, 77, 103-112.

Techera, E. (2021) “Deforestation, climate change and the emergence of legal responses: the international influence of Pierre Poivre’s environmental leadership”, forthcoming, Royal Society for Arts & Sciences of Mauritius/Académie des Sciences et des Belles Lettres of Lyon

UNEP (2015) Green Economy Assessment: Mauritius, https://www.greengrowthknowledge.org/national-documents/green-economy-assessment-mauritius

![D9B2E007-8D6A-4A47-8CE0-BBB63519FA47[4794]](https://charlestelfaircentre.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/D9B2E007-8D6A-4A47-8CE0-BBB63519FA474794-696x328.jpg)