Anouchka Sooriamoorthy, Docteur ès lettres de la Sorbonne

Les hommes entretiennent un rapport paradoxal, voire schizophrène à la mer. Elle est vénérée, adulée, crainte, en même temps qu’elle est salie, dénigrée, pillée. Depuis aussi longtemps que les productions artistiques nous permettent de le constater, la puissance de la mer, son immensité, sa part inconnue, la diversité de son écosystème fascinent : la mythologie grecque, peut-être la première, a décrit la force incommensurable de l’élément marin[1], de nombreux écrivains et poètes[2] ont en fait leur muse, les peintres et les réalisateurs[3] ont voulu saisir son esthétique. La mer n’est pas uniquement l’apanage des artistes ; pour de nombreux hommes, elle est un lieu de ressources, de divertissement ou de recueillement. Il semble ardu de comprendre comment cette admiration mêlée de dévotion n’a pu empêcher la grande violence des actions humaines envers la mer : pollution massive, surexploitation des ressources marine, destruction irréversible de l’écosystème[4].

Le constat n’est pas nouveau, il est même redondant : scientifiques et activistes écologiques prennent régulièrement la parole pour interpeller les dirigeants politiques, les industriels et les citoyens, mais cette parole est réduite à un cri inaudible au milieu de l’océan. Nous tenterons d’une part d’expliquer cette dichotomie schizophrène dans notre rapport à la mer, pour ensuite proposer une éthique de la mer ainsi que les modalités possibles de son application.

Comprendre la violence humaine envers l’élément marin

L’homme maître et possesseur de la nature

Notre rapport à la nature est indissociable de notre lien à la connaissance. Pendant longtemps, l’homme se trouvait dans une position de soumission et d’acceptation des éléments naturels : l’ordre du monde était ainsi, il fallait le respecter et le perpétuer. Au XVIIème siècle, la fin du Moyen-âge et de l’obscurantisme a suscité une soif de connaissances. René Descartes est, en Europe, l’un des philosophes qui illustre le mieux l’esprit de l’époque. Toute son œuvre est animée par la volonté d’établir une voie sûre afin d’atteindre la vérité et de proposer des fondements solides aux sciences. En prouvant que l’homme est le seul être doté de la faculté de la conscience, faculté qui lui permet non seulement de penser le monde, mais aussi de se penser, Descartes prouve en même temps que l’homme est supérieur aux autres êtres vivants, ces derniers étant dépourvus de conscience[5]. Dans le Discours de la méthode, Descartes décrit la voie pour atteindre la vérité dans les sciences : les connaissances acquises permettent de vaincre la superstition et les croyances pour fonder des bases scientifiques sûres. Grâce à une telle entreprise, l’homme est désormais « maître et possesseur de la nature[6] ». Cette maîtrise et cette possession permettraient, selon Descartes, le contrôle des productions de la terre et donc de notre alimentation, ainsi que la « conservation de la santé[7] » grâce au déploiement de la médecine.

L’homme maître abusif et possesseur égoïste de la nature

Cependant, les conséquences d’une telle affirmation ont probablement dépassé ce que Descartes aurait pu envisager : l’homme s’est transformé en maître abusif et possesseur égoïste de la nature. « Cette phrase est devenue le manifeste de la démesure humaine […], alors que pour Descartes, elle exprimait un rêve de libération de l’homme de l’emprise d’explications magiques de la nature, de voir enfin arriver le règne de l’homme qui allait pouvoir avoir une maîtrise de son environnement[8] » L’accumulation des connaissances et le développement de la technologie ont généré une idolâtrie irrationnelle du progrès : il faut conquérir tous les territoires, laisser la trace de l’homme partout. Aveuglé par des innovations scientifiques et technologiques sans précédent, l’homme du XXIème siècle a oublié qu’il vient de la nature et qu’une exploitation sans limite de cette dernière engendrerait une disparition certaine de la nature, mais aussi de la nature humaine. Le désir de connaissances s’est transformé en arrogance de tout savoir. Au XVIIIème siècle, le philosophe Jean-Jacques Rousseau mettait en garde contre le demi-savant ou celui qui détient l’illusion de la connaissance :

« Il est de la demi-science en fait d’esprit comme de l’hypocrisie en fait de mœurs. Le demi-savant n’a que le masque de la science, comme l’hypocrite a le masque de la vertu. Ils jouent l’un et l’autre, l’un la vertu, l’autre la science. Et comme l’hypocrite va au vice par le chemin de la vertu, le faux savant, le demi-savant, car c’est le même homme, va à l’ignorance par le chemin de la science. Il n’est pas nouveau de dire que la demi-science est pire que l’ignorance.[9] »

L’homme s’est paré d’arrogance, oubliant les limites de sa conscience qui ne peuvent lui permettre de tout savoir, de toujours anticiper et de prévoir sur un long terme les conséquences de ces actions. Faisant fi des limitations, armé des outils de la technologie, l’homme s’est pris pour la puissance divine voulant tout contrôler, tout soumettre. C’est ainsi que nous sommes passés du statut d’adorateur à celui de destructeur de la nature.

Poser un cadre éthique

« La thèse liminaire de ce livre est que la promesse de la technique moderne s’est inversée en menace, ou bien que celle-ci s’est indissolublement alliée à celle-là. Elle va au-delà du constat d’une menace physique. La soumission de la nature destinée au bonheur humain a entraîné par la démesure de son succès, (…), le plus grand défi pour l’être humain(..).[10] »

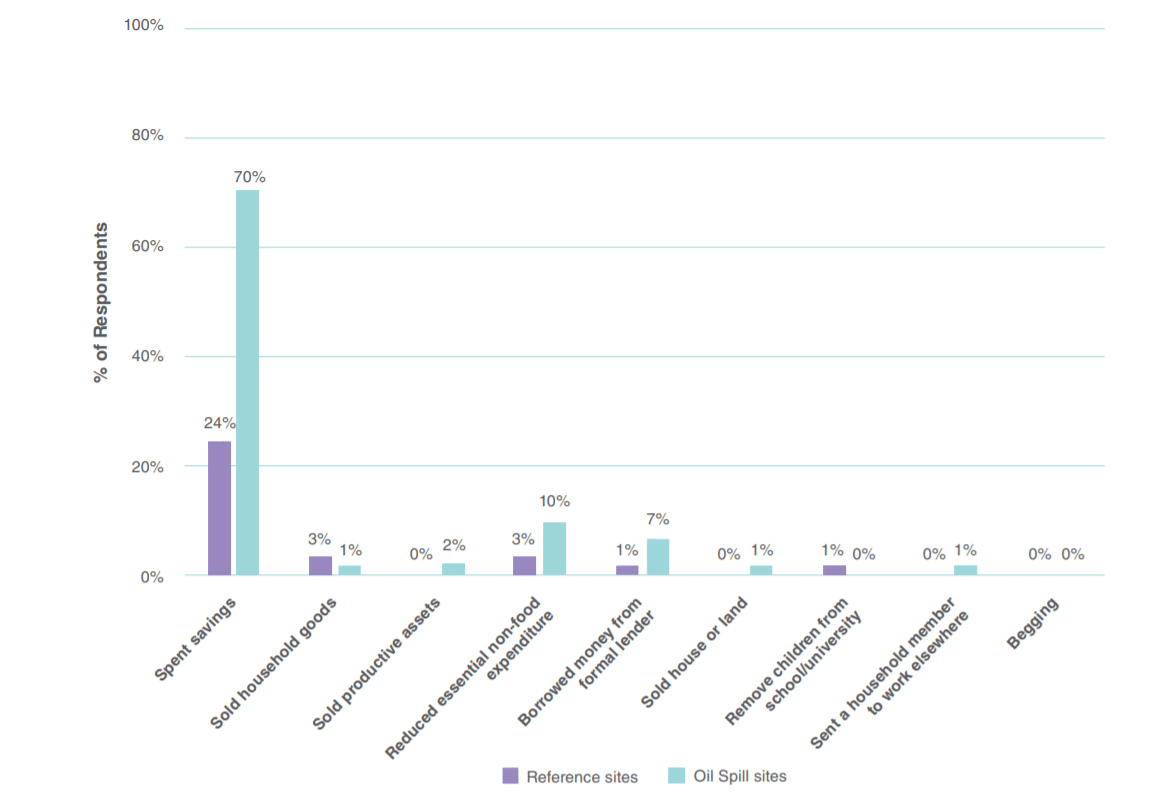

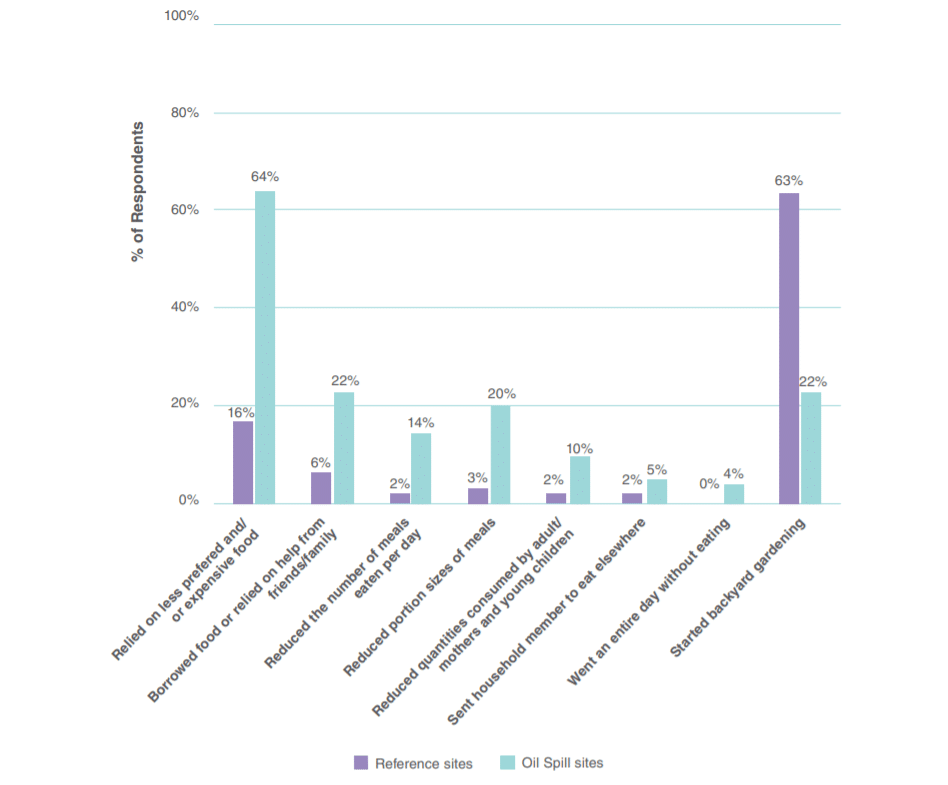

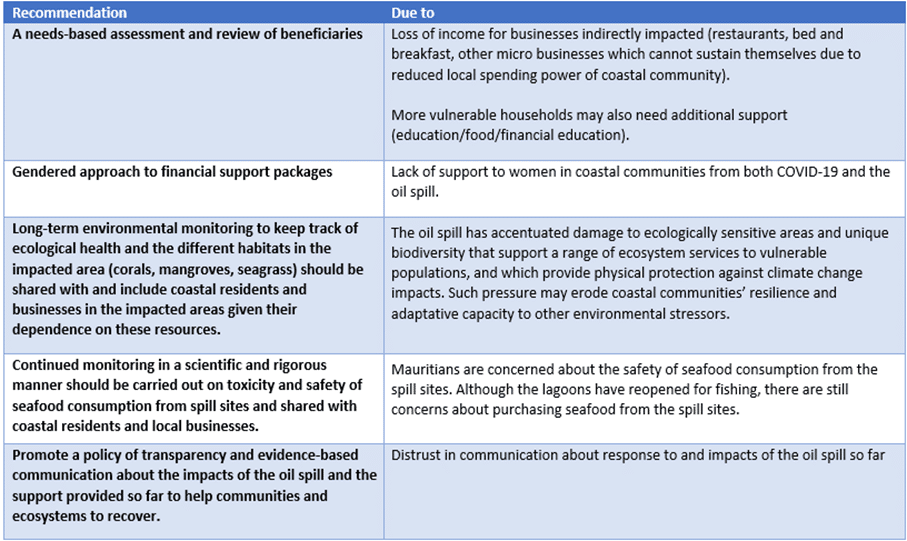

Ces phrases sont tirées de la préface de Pour une éthique de la responsabilité de Hans Jonas, ouvrage publié en 1979 qui peut être considéré comme le premier à aborder la notion d’éthique écologiste. Plus de quarante ans après sa publication, les propos de Jonas sont d’une édifiante actualité. La glorification de la technologie et de la modernité a été remplacée par le règne de la peur : marées noires, déversements de produits dangereux dans les eaux, destruction massive des fonds marins par les filets de pêche industrielle, surexploitation de la pêche et déséquilibre de l’environnement due aux grands complexes industriels.

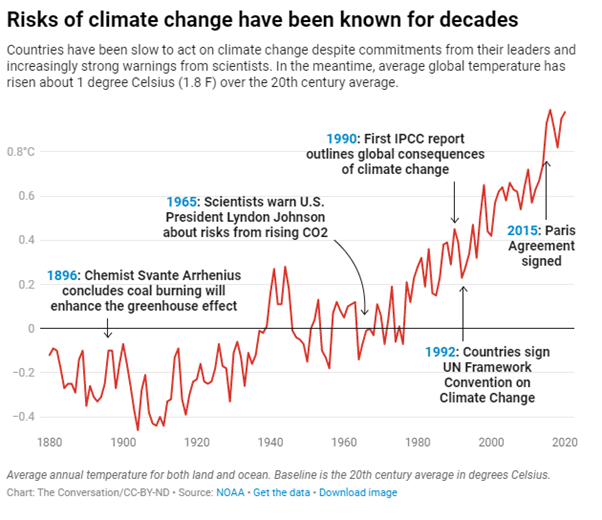

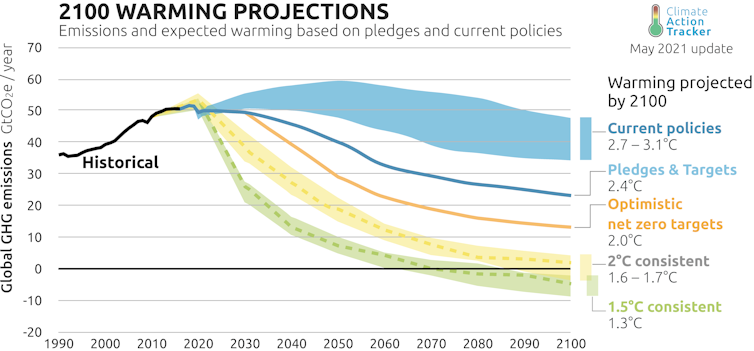

Là où, il y a quelques années encore, ces propos catastrophistes pouvaient être balayés d’un revers de main au nom d’une indifférence envers la nature et d’un égoïsme assumé, les multiples études et rapports[11] ne permettent plus une telle attitude, car parmi les victimes, se trouve l’homme : maladies environnementales, appauvrissement des familles de pêcheurs, migration économique forcée, détérioration de la quantité et de la qualité des ressources marines. Si l’homme est un être égoïste, son égoïsme devrait créer un réveil de la conscience afin qu’il se protège des dangers qu’il a lui-même orchestrés. L’argument de l’ignorance (on ne savait pas) ou celui du relativisme (libre à chacun d’agir comme bon lui semble) ne sont plus, devant l’urgence de la situation, recevables. Devant un constat aussi désespérant, si rien n’est mis en œuvre, le risque est de sombrer vers une lente et réelle misanthropie, jusqu’à souhaiter la disparition de la nature humaine pour permettre une réappropriation de ses droits par la nature, réappropriation à laquelle l’homme ne pourrait assister, car son absence en serait justement la possibilité.

Une éthique de la responsabilité

Jonas analyse que, devant l’ampleur de la menace, une éthique traditionnelle serait inefficace, il faudrait penser une éthique qui ne repose pas uniquement sur l’intention, mais sur les actes. C’est ainsi que Jonas propose de fonder une éthique de la responsabilité qui reposerait sur le principe suivant :

« Agis de façon que les effets de ton action soient compatibles avec la permanence d’une vie authentiquement humaine sur Terre.[12] »

A la violence de l’agir humain est opposé la responsabilité de la conscience : il y a une obligation d’agir pour pérenniser la vie humaine sur terre. Un rapide survol des études sur le sujet indique que cette pérennisation ne présente aucune garantie : 90% des gros poissons ont disparu depuis la pratique de la pêche industrielle et d’ici 2050 les mers pourraient être intégralement vidées de poissons[13]. A la peur alimentaire, se rajoute l’incertitude devant un tel dérèglement initié par l’homme, dérèglement d’une ampleur sans précédent dans l’histoire humaine. La maxime proposée par Jonas doit être appliquée par tous sans exception, condition sine qua non pour qu’elle puisse permettre une certaine efficacité. Cependant, l’égoïsme naturel de l’homme, son ignorance, son penchant à une forme d’aveuglement volontaire sont autant de travers qui peuvent faire douter de la mise en pratique universelle et sans condition de cette maxime. Une éthique sans modalité d’application demeure une coquille théorique vide.

De l’éthique au juridique

C’est au domaine juridique d’incarner l’application pratique du principe éthique. Dès les années soixante, surgit l’idée d’accorder des droits à la nature. En 2007, la constitution équatorienne est la première en son genre à reconnaître les droits de la nature. Cependant, une telle démarche ne parvient à s’écarter d’une perspective anthropocentrée : ce sont en effet les hommes qui décident du type de droits à accorder aux éléments naturels et des modalités de la mise en place de ces droits. Pour le philosophe et juriste François Ost, la protection juridique de la nature doit être mise en œuvre par l’attribution de devoirs imposés aux hommes. : « Des devoirs asymétriques de responsabilité, justifiés à la fois par la vulnérabilité des bénéficiaires et par la nécessité de respecter les symbioses biologiques dans l’intérêt de l’humanité entière.[14] » L’asymétrie des devoirs décrite par Ost n’est en rien injustice : celui qui détient une conscience plus élaborée détient en même temps l’obligation de l’utiliser de façon morale face à ceux qui en sont dépourvus (le monde animal, la mer, la nature). En adoptant une telle visée, la conscience ne peut plus légitimiser la violence ; au contraire, elle oblige une responsabilité en acte.

Cependant, tant qu’un droit écologique international ne sera pas pensé, l’application stricte d’une telle éthique de la responsabilité avec les devoirs juridiques qui en découlent peut sembler relever d’une utopie. Devant la complexité d’harmoniser les pratiques juridiques dans les domaines commerciaux ou familiaux par exemple, nous pourrions afficher un certain scepticisme quant à la possibilité de la mise en pratique d’un tel projet juridique. Si l’instauration d’une telle éthique de la responsabilité ne peut être réduite à un niveau national (comment penser dans le cadre de frontières ce qui n’a pas de frontières ?), son application à l’échelle planétaire semble un doux rêve. Une telle mise en œuvre serait d’abord de la responsabilité des pays de la mer : les îles et les pays avec un littoral. Si la problématique marine concerne tout le monde, la mise en application d’une éthique de la responsabilité devrait débuter par ceux qui ont la plus grande proximité géographique avec la mer. Cette mise en pratique pourrait prendre au moins deux formes. Premièrement, celle de l’exemplarité : dans les comportements, dans les habitudes, dans les principes pédagogiques transmis, dans les visions politiques adoptées. Si ceux qui voisinent l’élément marin ne manifestent pas un souci constant de protection, il sera difficile d’exiger une telle attitude de la part des pays sans littoral. En se posant, non avec prétention, mais avec un souci d’universalité et de pérennisation, en exemple à suivre, les pays de la mer dessineront, il faut en faire le pari, les contours d’une posture nouvelle à adopter. Deuxièmement, une constitution marine commune aux 150 pays de la mer devra être pensée. Le fondement d’un tel texte juridique ne serait pas économique ou géopolitique comme l’est la plupart des regroupements actuels de pays (G20, OTAN, MERCOSUR etc.), mais reposerait sur le respect et la permanence de la mer. Interdisciplinaire et transversale, cette constitution se nourrirait de savoirs philosophiques, juridiques, scientifiques, mais aussi de l’imaginaire des artistes et du vécu des hommes de la mer. Une telle constitution marine illustrerait ainsi l’esprit de la phrase du poète caribéen Edward Kamau Brathwaite : « The unity is sub-marine[15]. »

Main Photo by Jeremy Wermeille on Unsplash

Charles Telfair Centre is an independent nonpartisan not for profit organisation and does not take specific positions. All views, positions, and conclusions expressed in our publications are solely those of the author(s).

[1] Si L’Odyssée d’Homère fait partie des premiers écrits sur la mer, le mythe de l’Atlantide illustre peut-être le mieux cette force marine contre laquelle on ne peut rien : l’île d’Atlantide est engloutie par les eaux le jour où ses habitants devinrent corrompus : « En l’espace d’un seul jour et d’une nuit terrible, tout ce que vous aviez de combattants rassemblés fut englouti dans la terre, et l’île Atlantide de même fut engloutie dans la mer et disparut. » Platon, Timée, 25d, Editions Flammarion, 2017.

[2] Il serait peut-être impossible d’effectuer une liste exhaustive des productions littéraires ayant pour thème la mer tellement elles sont nombreuses. Le Vieil homme et la mer d’Ernest Hemingway (1952) et le poème L’Homme et la mer de Charles Baudelaire (in Les Fleurs du mal, 1857) dont le premier vers, « Homme libre, toujours tu chériras la mer ! », est un hommage exalté, demeurent parmi les plus connus.

[3] L’immense succès rencontré par le film Les Dents de la mer, réalisé par Steven Spielberg, à sa sortie en 1975 en fera par la suite un classique du cinéma.

[4] Le documentaire à charge Seaspiracy réalisé en 2021 par Ali Tabizi dénonce les conséquences des actions humaines sur l’élément marin. Malgré certaines critiques concernant la validité de certains faits énoncés, le documentaire a rencontré un important succès.

[5] Il s’agit de la théorie du « Cogito ergo sum » traduite par « je pense donc je suis », exposée dans le livre 1 des Méditations métaphysiques.

[6] René Descartes, Discours de la méthode, tome I, sixième partie, Editions Flammarion, coll. GF philo, 2020.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Marie-Frédérique Pellegrin dans l’émission « Les Chemins de la philosophie » du 24 février 2021, sur France culture

[9] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Lettres philosophiques, « Lettre XL », in Œuvres complètes, tome 32, 1796

[10] Hans Jonas, Le Principe de responsabilité, Editions du Cerf, 1979

[11] Le dernier rapport du GIEC (Groupe d’Experts Intergouvernemental sur l’Evolution du Climat), publié le 9 août 2021, indique une diminution du pH moyen des océans en raison de la dissolution du C02 dans l’eau, la conséquence étant une acidification des océans qui menace de nombreuses espèces de plantons, base de la chaîne alimentaire océanique.

[12] Ce principe prend modèle sur les impératifs catégoriques du philosophe Emmanuel Kant qui visent à penser une morale universelle et irréfutable.

[13] “Rapid worldwide depletion of predatory fish communities”, par Ransom Myers et Boris Worm, revue Nature N°423

[15] L’unité est sous-marine.

![]()

![D9B2E007-8D6A-4A47-8CE0-BBB63519FA47[4794]](https://charlestelfaircentre.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/D9B2E007-8D6A-4A47-8CE0-BBB63519FA474794-696x328.jpg)