Rachel Moussié – Deputy Director, Social Protection Programme, WIEGO

In this article, Rachel Moussié explores how gender-responsive social protection policies can prevent deepening inequalities now and contribute to a more resilient system prepared for future shocks in Mauritius. The article proposes to expand the benefit package and harmonise existing social protection schemes so they can better protect and reach women with low incomes, working in either the formal or informal economy. Drawing on examples from other upper and middle-income countries, the intention is to propose policy options for discussion among social partners, civil society, researchers, and development partners.

In the current COVID context significant risks of job losses for women and men have led to numerous emergency social protection measures aimed at supporting Mauritian workers both in the formal and informal economy. Recent post-Covid statistics show growing gender inequalities in the Mauritian labour market. This is undoing the timid progress made so far on women’s economic empowerment in the country and is exposing more women and children to poverty and violence. For a small island reliant on its skilled labour force, growing gender and class inequalities pose a great risk to social cohesion, economic recovery and further development. The pandemic underscores how economic recovery, employment and social protection are interdependent and mutually reinforcing, making social protection an important development tool. Drawing on examples from other upper and middle-income countries, the article proposes a non-exhaustive set of gender-responsive social protection policies that expand the benefit package and harmonise existing social protection schemes to better protect women and men with low incomes working in the formal and informal economy.

The Gender Gap

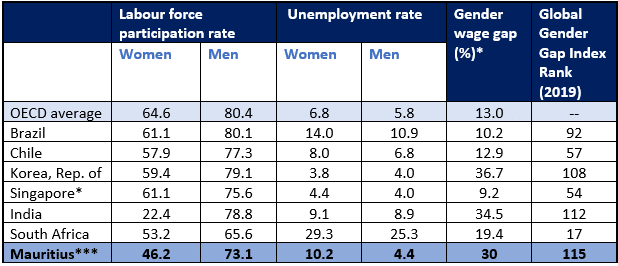

Mauritius is behind other high and upper-middle income countries when it comes to gender equality (see Table 1). The gender wage gap in Mauritius is triple that of Singapore. Because of women’s low economic empowerment and opportunity and low political empowerment, Mauritius only scored 115 out of 153 countries on the 2020 Gender Gap Index.

These inequalities are made worse by the economic downturn brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic through three channels:

More women than men become inactive: While, by July 2020, more men than women have lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic, by September 2020, men had returned more rapidly to the labour market post-lockdown, while women were more likely to become inactive. Between the first quarter of 2020 and July 2020 there has been a 6.2% increase in the inactive population among women compared to only 2.5 per cent increase among men.

Women bear an increased unpaid care work burden: Evidence suggest that women take on even more unpaid care work during an economic crisis – rather than purchasing care services, cooked food or clothes, women will provide these goods and services in their own homes by spending more time caring for children or the elderly, cooking, or mending and recycling clothes. This reduces women’s time for paid work, negatively impacts their wellbeing and leads to poorer quality care for children and other dependents as household incomes fall permanently.

Women informal workers face constraints in accessing social protection programmes: Informal wage and non-wage employment were at lower levels in September 2020 than formal wage and non-wage employment, suggesting that a large proportion of the jobs lost during the crisis were in informal employment. Recent research on vulnerable informal women entrepreneurs found that 88 per cent of their sample had no social protection coverage, the remaining 12 per cent benefited from the Basic Retirement Pension and/or the National Pension Fund as they were at least 60 years old. Low education, lack of information and the complexity of administrative processes were key barriers faced by women for business registration and inclusion in social protection programmes. The research findings confirm that poverty-targeted cash transfers available to those on the Social Register exclude the working poor many of whom are informal workers – leaving them with no social protection coverage during their working lives.

Hence, as women face increasing constraints to access paid employment, there is an urgent need for a more gender-responsive social protection system.

What policy options exist?

Maintaining the universal Basic Retirement Pension

The Mauritius Basic Retirement Pension is gender responsive and redistributive as it significantly contributes to income security among older women who have a higher life expectancy and are likely to have i) contributed less to social insurance schemes due to lower earnings and wages, ii) taken time off from paid work due to their unpaid care work responsibilities at home, iii) found work in the informal economy, iv) or never participated in the labour market. A universal social pension protects the elderly and entire households from poverty and food insecurity during crises – acting as an economic and social stabiliser. It guarantees women and men will receive the same social pension regardless of their contribution rate and whether they work in the formal or informal economy. This is a redistributive measure that allows for the risks brought on by an aging population and climate change to be borne more collectively.

In June 2020, without prior consultation with the social partners, the government announced a shift away from a funded pension system, the National Pension Fund, to a pay as you go pension system through the Contribution Sociale Generalisée (CSG). Contributions to the CSG are currently intended to cover pensions and will be supplemented by tax revenue to finance the Basic Retirement Pension.

Expanding the benefit package

While the debate is still open on the viability of the chosen financial model for the CSG, expanding the benefit package of the CSG beyond a pension to include an unemployment benefit and maternity and paternity leave benefits could incentivise more informal workers to register and contribute to the CSG. The advantages are multifold, i) it increases overall financing for the CSG, ii) it enables the formalisation of informal workers and enterprises and iii) it enhances social solidarity as contributions from the formal economy subsidise those from the informal economy.

Unemployment benefit: In 2019, the Mauritius Workfare Program covered 23 per cent of workers in the formal economy and only three per cent in the informal economy. Men are almost twice as likely to participate in the program than women, and older workers are four times more likely to participate than younger workers. The program eligibility criteria requires full-time employment for at least 18 months. Women workers are more likely than men to work part-time due to their care responsibilities at home and younger workers may not have 18 months of experience in the same job.

Eligibility for the Workfare Program should be relaxed so more women, youth and informal workers can benefit. The CSG could partially cover the costs of expanding the Workfare Program in addition to tax revenue. Those workers who contribute to the CSG could receive a slightly higher benefit amount through the Workfare Program than those who do not – incentivising informal workers to contribute to the CSG though not excluding those who cannot contribute. This transforms the Workfare Program from a non-contributory benefit to one partially based on contributions. It would require a financial assessment of the CSG.

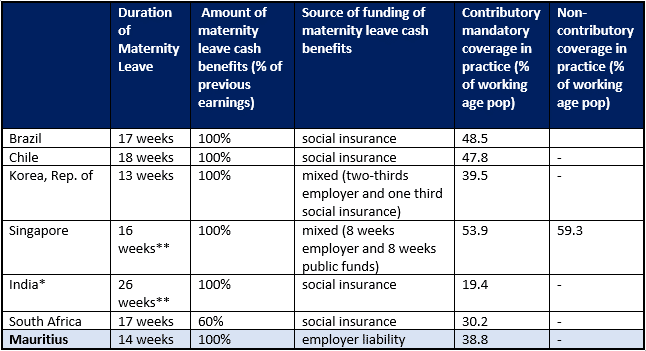

Maternity and paternity leave and benefit: Mauritius is behind other high income and upper-middle countries in its parental leave policies. A first step to improve maternity and paternity protections is to finance this through social insurance or public funds rather than employer liability. The latter discourages employers to hire and retain women during their prime reproductive years and is one more barrier for women to stay in employment once they have children. Most high and middle-income countries rely on social insurance or a mix of employer liability and social insurance/public funds to cover maternity leave and benefits (see Table 2).

Moving towards contributory maternity protections redistributes the costs of hiring and retaining women for an individual employer to all workers and employers and across small and large firms. Given Mauritius’ low and stable fertility rate of 1.4, the associated costs should remain manageable.

In Singapore, the parental leave benefits are available to employees and self-employed workers in continuous employment for at least three months before the birth. The two-week paternity leave benefit is paid entirely by the state with no employer liability. To encourage shared-parental responsibility, the government allows for working fathers to share up to four weeks of their wives 16 weeks of maternity leave.[1]

Simplification and harmonisation of contributions

The CSG could integrate the Workfare Program, maternity and paternity leave benefits and the Basic Retirement Pension into a unified social protection benefit package. All workers’ and employers’ contributions would go towards financing this bundle of social protection measures. The CSG currently proposes to include self-employed workers through a Rs 150 ($4) contribution, this could constitute the first tier of a ‘monotax’ payment and registration system for micro-enterprises as used in Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. A monotax combines tax revenue and social security contributions into one simplified payment for low-income earners in the informal economy that gives them access to pensions, maternity and unemployment benefits.

It is noteworthy that the implementation of the Self-Employed Assistance Scheme allowed informal workers to register with the Mauritian Revenue Authority for the first time and set up mobile and online banking services. This demonstrates the potential for the formal registration of informal activities through a harmonised CSG.

Harmonisation, equity and recovery

Expanding and harmonising benefits through the CSG must go hand in hand with greater representation of women workers in the formal and informal economy in a CSG governed by a tripartite structure. Financing the CSG is a concern given the declining active labour force, an aging population, the low fertility rate and the economic transformation needed towards low-carbon sectors. It has been argued that higher employer contribution rates threaten Mauritius’ status as a low-tax jurisdiction. However, other low-tax jurisdictions such as Singapore and Ireland have far higher employer contribution rates and more comprehensive social protection systems. A more equitable and gender responsive redistribution of wealth is central to a stronger social protection system that will allow Mauritius to recover and prepare for future shocks.

[1] The policy is discriminatory as the full benefit levels are only available if the child is a Singaporean citizen and the parents are married. This discriminates against migrant workers whose children are not Singaporean citizens and single mothers who only receive 12 weeks paid maternity leave.

The Charles Telfair Centre is non-profit, independent and non-partisan, and takes no specific position. All opinions are those of the authors/contributors only.