Myriam Blin, Head of the Charles Telfair Centre, Charles Telfair Campus [1]

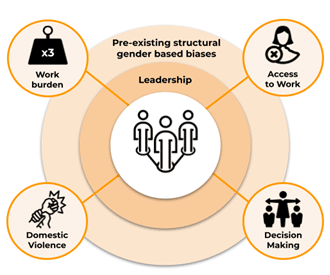

In this article, Myriam Blin, Head of the Charles Telfair Centre reviews the gendered structures still permeating women’s lived experiences at home and at work. Despite tremendous progress on the gender front over the last 30 years, entrenched inequalities rooted in gender and cultural norms rouse fears that, unless gender responsive policies are implemented, the gender inequalities will be exacerbated in the current crisis, notably through four main channels: work burden, domestic violence, access to work and decision making. As we celebrate the 110th International Women’s Day on the theme Women in Leadership, she proposes five key sources of biases we can choose to challenge to support a gender inclusive economic recovery.

Covid-19 continues to be unquestionably devastating as we see the global death toll rising with multitudes of strains creeping their way out of the woodwork and making the economic outlook decisively uncertain. The unfolding crisis is having a deleterious impact on businesses and families across the world, but while the crisis affects almost everyone in one way or another, evidence is mounting that women are disproportionately impacted with regards to their work and wellbeing.

Mauritius has seen tremendous progress in advancing women’s economic opportunities and reducing the gender gap over the last 30 years, yet, entrenched inequalities rooted in gender and cultural norms rouse fears that, unless gender responsive policies are implemented, the gender inequalities will be exacerbated in the current crisis.

As we celebrate the 110th International Women’s Day on the themes Women in Leadership and #ChooseToChallenge, I propose five key sources of biases we can choose to challenge to support a gender inclusive economic recovery.

Mind the Gap

While Mauritius fares relatively well in gender responsive legislation, it only ranked 115 out of 153 countries on the Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI). There is increasing evidence that the gender gap in Mauritius is widening once more as the crisis cascades through four main channels: work burden, domestic violence, access to work and decision making.

Women’s work burdens

Women’s traditional gender role confines her to the private sphere reflecting entrenched patriarchal values that assign home care responsibilities predominantly to women. In Mauritius, women’s perceived gender role within the home persists: 68% of Mauritians believe it is better if women (as opposed to men) take care of the household and 44% believe men have more rights to a job than women when jobs are scarce. In 2019, Mauritian women spent close to 20% of their time on household chores and unpaid care activities compared to just under 5% for men. Recent evidence also suggests that the crisis is worsening parental mental load, which disproportionately affects women compared to men.

In times of crisis, households substitute what would have been purchased outside by producing these goods and services at home, a burden that disproportionately falls on women. The compounding of women’s work burden negatively impacts their well-being and their ability to stay in paid employment. Early data from the Continuous Mauritius Multipurpose Household Survey (CMPHS) shows that while women and men have both been affected by job losses, most men have remained on the labour market whereas women have largely exited with the activity rate among women declining by 2.7 percent between Q1 2020 and July 2020. The human cost is largely a female one as we see the severe economic downturn slowly eroding progress made in female labour force participation in the last decade.

Home is not safe for everyone

Twenty four percent of women in Mauritius have experienced some form of domestic violence (data from 2012) and in 2019 7.3% of Mauritians believed it is justified for a man to beat his wife. As men and women lose their jobs, as economic insecurity increases and mental health deteriorates, domestic violence escalates. Domestic violence is a product of a deeply unequal world that pre-dates the COVID-19, but the lockdowns intended to protect the public saw positive correlations with domestic violence, and for some women these safety measures turned into a death sentence. Mauritius has been no exception: between March and May 2020 there has been a 4% increase in the number of reported cases of domestic violence compared to the same period in 2019. Just for the month of May 2020 (post-lockdown) there has been a 47% increase in reported cases compared to May of the previous year – close to 93% of the reported victims were women.

Women in the Workforce

A 2018 world bank working paper estimated that 57 % of Mauritian women participated in the labour force compared to 89% of men. While female labour force participation has increased by 7 percentage points in the last 10 years, the data reveals a strongly gendered labour market:

- Marriage, childbirth and childcare are all factors pushing women out of the labour market and only 53% of married women engaged in the labour market.

- In the private sector men are disproportionately represented in high-skill jobs, despite more women than men completing university.

- On average women only earn 76% of what men earn, and a substantial proportion (78%) of the gender wage gap cannot be explained by differences in productivity, education, or position – indicative evidence that the wage differential is rooted in explicit or implicit bias.

- Highly educated women tend to be disproportionately employed in low-and mid-skill jobs compared to men.

- Despite a larger increase in unemployment for men compared to women in 2020 due to the covid-19 crisis, women face more difficulties in obtaining a job with unemployment systematically higher for women than for men over the last 20 years.

Key to the concept of empowerment is, arguably, the relation to human dignity, the dignity that comes from being productive and the freedom to express one’s potential. Yet, gender norms and patriarchal values that assign women to traditional gender roles together with implicit and explicit bias pull women away from the labour market and leadership roles and pushes them into sectors and job functions that are more “compatible” with their homecare responsibilities. The current crisis is exacerbating the trend: a significant proportion of women are not returning to work after losing their employment or choose a less demanding and lower paid career path with greater flexibility to manage their increased work burden.

Women and decision making

With only 18% of parliamentary seats held by women, 5% of private sector leadership positions held by women and only 8.7% of board members being women, the Mauritius gender glass ceiling is very much alive and several inches thick. Thirty six percent of companies reported that “gender equality” was included in their internal policies for recruitment and promotion, yet the number of men in senior positions (C-suite) is almost five times higher than that of women.

Firms that are diverse and inclusive outperform those that are not. Being diverse and inclusive does not simply mean ensuring that a certain number of women sit on leadership tables (evidence actually suggests that having a small minority of women on a leadership table has limited impact). It requires a systemic review of sources of bias and a collective plan that engage employees into the process of identifying how to address explicit and implicit biases at all levels of the organisation.

With 10% or less of women in senior level teams at entities such as the Ministry of Finance, Economic Development Board or Business Mauritius, women continue to be excluded from economic recovery high-level decision-making. Such exclusion only serves to undermine recovery efforts for society as a whole.

Putting on Gender Glasses: Five avenues to challenge gendered structures in Mauritius

1. Challenge gender norms at home and at work

Women’s work burden, domestic violence, labour market barriers including the glass ceiling are all rooted in social constructions of what constitute the feminine and masculine. We have tools at our disposal to challenge these gender norms:

- Embedding gender programmes into the education system

- Running national gender awareness campaigns on masculinity, gender division of roles, domestic violence and women in leadership.

- Bringing men and women together at work, at home and at schools as allies in fighting sources of gender inequality.

2. Challenge the idea of gender-neutral policies:

Nothing is neutral and most certainly not the gendered implications of covid-19 in Mauritius. What is often conceived as neutral (i.e. having the same impact on men and women) is in fact masculine if decision making fails to take into account women’s specific socially constructed contexts. Eschewing neutrality in favour of improving understanding of the intersectionality of Mauritian women’s identities and experiences will allow government and corporate organisations to craft effective policy responses that achieve gender mainstreaming. A good start is implementing policies that ease women’s roles as primary caregivers:

- Implementing extended paternal and paid maternity leave and make the government share the cost of maternity leave

- Extending subsidised child-care facilities for children under the age 5.

- Implementing flexible work practices that can ease pressure on women’s work burden. The COVID-imposed remote work has shown the potential of flexible arrangements which, with the right conditions, can boost performance up to 13%.

3. Challenge the current gendered leadership culture:

Work is where men and women interact for a great proportion of their daily lives – it is both a perpetuator of gendered structures as well as a potential disruptor of social ones. Gender inclusion is not just good intrinsically, it is also good for the economy and the performance of an organisation. Private organisations and government entities need to go further and fundamentally challenge their structures, work practices, systemic biases to profoundly transform organisational cultures and values for greater equitability. They have a responsibility to provide women specific support mechanisms, including mentoring and the implementation of quotas, to allow them a fair playing field in their career path. Programmes such as LeanIn, Champions of Change Coalition, the UNDP-AUC African Young Women Leaders Fellowship Programme are examples of starting points for creating networks of solidarity for female (and male) allyship.

4. Challenge the gap in gender related data:

We can only truly assess and evaluate the extent and complexity of the gender gap if systematic and frequent gender disaggregated data is collected and shared: in the absence of data researchers cannot assess the complexities behind gender inequality, and NGOs and policy makers cannot make informed decisions. Mauritius does not collect data on 50% of GGGI indicators. Statistics Mauritius needs to up their game and implement a systematic policy of gender data disaggregation wherever relevant to allow for the theorisation of precarity in the context of Mauritius. Similarly, the government, as undertaken in the UK and Denmark, could require public and private organisations to disclose their gender disaggregated pay statistics to help fight the gender pay gap.

5. Challenge the weak enforcement of gender related legislation

Mauritius has fared relatively well on the Social and Institution Gender Index, but evidence suggests that there are structural weaknesses preventing the proper enforcement of the legislation, notably those pertaining to domestic violence, workplace harassment and employment discrimination (e.g. difference in promotions and earnings). HR departments, the police force and courts need to challenge their current practices and implement adequate processes and mechanisms to allow safe and effective reporting of incidences of violence, harassment, or discrimination across the relevant institutions.

Allyship

The empowerment of women is not solely a women’s issue but a societal one and it is important to note that the socialisation of gender stereotypes hurts men and women. Both sexes are bearers of social identities situated at a nexus of gender, class, age, race, ethnic-identity and religion, all of which add further complexity to the sources and processes of bias against women in Mauritius. Challenging norms, stereotypes and patriarchy are at the heart of any effort to fight gender inequality and it is through our combined efforts and the building of allyship between men and women that gender discrimination can become history. So, let us support our women and girls as the carriers of our collective futures as we seek to unlearn gender bias in order to build resilient economies that are kinder and fairer for everyone.

[1] I would like to thank the two reviewers and the editor for their constructive and encouraging feedback.

Main photo by WIPO on Flickr, CC licence

The Charles Telfair Centre is non-profit, independent and non-partisan, and takes no specific position. All opinions are those of the authors/contributors only.