Paul R Baker, Founder and Chairman, International Economics Consulting Ltd (IEC)

Taahirah Zahraa Boodhoo Beeharry, Policy Researcher, International Economics Consulting Ltd (IEC)

Loan Thi Hong Le, Managing Director of International Economics (Vietnam office)

Why the interest in CBDCs in Africa?

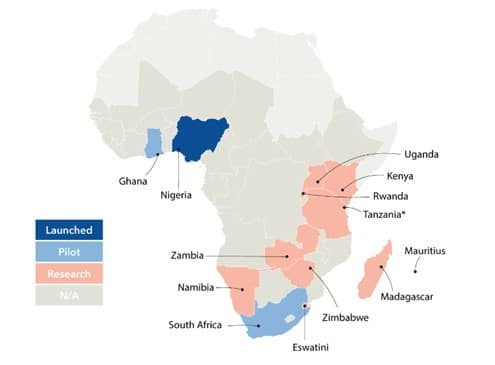

With the rapid proliferation of cryptocurrencies and the emergence of new digital currencies, national governments are increasing efforts to provide more stable and regulated alternatives to private sector-driven initiatives. Central bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) have garnered considerable interest amongst many governments worldwide, having been implemented by several developing countries and piloted in many others, including the European Union (EU), the US, and several African countries [1]. Nearly a dozen countries across the continent are considering their options concerning implementing CBDCs.

There are widespread benefits from the implementation and use of CBDCs. In the African context, one of the most significant achievements of CBDCs would be to lower the costs of transactions within the region. CBDCs can reduce transaction fees and merchant fees. Moreover, by lowering the costs of cross-border transactions, CBDCs are expected to encourage further trade between African countries and contribute to expanding regional value chains.

What are CBDCs?

In essence, CBDCs are the digital version of traditional fiat money. They are issued, regulated, and backed by central banks. Unlike cryptocurrencies and stablecoins, where there is almost no government oversight, CBDCs are centralised and operate within the regulatory framework of a government’s financial system. Therefore, they are more stable and secure than cryptocurrencies and stablecoins. There is a wide range of possibilities for governments to design their CBDC system. Examples include an account-based model where customers open deposit accounts with the central bank or private sector models where private institutions continue to act as intermediaries between the central bank and consumers (see Figure 2). Although the existing use of cryptocurrencies across the continent may represent some form of competition for CBDCs, the two currencies are fundamentally different in their design, purpose, and underlying technology. While CBDCs are designed to work within existing financial systems, cryptocurrencies are designed to operate independently of them. Nonetheless, they are likely to coexist as separate forms of digital currency.

CBDCs can ease transaction costs and shorten transaction times

One of the key benefits of CBDCs is their potential to reduce transaction costs in Africa. At present, the cost of cross-border payments in Africa is significantly higher than the global average. As per estimations of the World Bank in September 2022, transaction fees represent 8.5% of the total value of remittances to African countries. In contrast, the transaction fee for global transactions amounts to only 6.5%, with South Asia having the lowest costs at 4.9%. The high costs of transferring money to and within African countries are driven by numerous factors, including the fragmented payment systems, poor governance and risk management among service providers, legal and regulatory barriers as well as a lack of competition in the payment ecosystem. African payment systems rely heavily on the correspondent banking system located outside the continent, which further adds to the cost. According to SWIFT (2018), North America remain the main clearing route for African financial flows. More than 80% of the transactions sent from Africa to the United States have their final beneficiary in another region, including 19.5% of which returns to Africa. In the past year, many different mobile money platforms have emerged in Africa. While this improves competition and creates a bustling digital payment ecosystem, it nonetheless complicates and lengthens the process of connecting different service providers, especially when the latter operates under different standards.

The payment ecosystem in Africa, dominated by numerous traditional commercial banks and inadequate infrastructure, is a hurdle to conducting business. In a survey conducted among 1,300 businesses in Africa, the conventional banking system was portrayed as having numerous deficiencies, including high costs, low speed, and unreliability. 32.1% of the businesses surveyed indicated that business-to-business payment methods were too expensive. Furthermore, while 41.2% of businesses report a day’s waiting time for payments to be credited to their accounts, many businesses reported having to wait for a week (39.5%).

By providing a more efficient and cost-effective alternative to transferring money, CBDCs could significantly reduce the cost of sending remittances, B2B transactions, and cross-border trade. The costs and time associated with cross-border payments are reduced by eliminating the need for intermediaries such as commercial banks or payment processors. CBDCs allow transactions to be carried out and reflected within seconds. Moreover, since CBDCs are backed by the Central Bank, these would instil greater confidence among traders and mitigate concerns over liquidity, credit risk and foreign exchange settlement risks that currently hinder cross-border payments.

CBDCs can improve intra-regional trade

CBDCs will allow greater scope for businesses, especially small enterprises, to trade across borders, thus boosting intra-African trade. With the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) coming into operation, CBDCs can further lower business costs between African countries. In light of the benefits of CBDCs, certain regional economic communities, such as the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) are considering developing a common digital currency. In the case of CEMAC, its digital currency is intended to be used across all six of its Member States, namely Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon. Moreover, CBDCs can also reduce dependence on the US Dollar as a common currency for trade. As certain African countries struggle to participate in international trade due to foreign exchange reserves, CBDCs provide an alternative, allowing countries to trade in their local currencies. For instance, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia are pursuing the possibility of a joint-digital currency, Project Aber, for use within and between the two countries. Thus, by facilitating cross-border trade, CBDCs offer an important avenue for increasing intra-African trade and deepening regional integration.

In addition to these benefits, it is also worth noting that CBDCs could potentially increase financial inclusion (and in some cases for the informal sector to integrate into the formal sector) and overhaul current payment systems. With greater uptake of CBDCs by the informal sector, CBDCs could shed light on the sizeable share of transactions that take place within the informal economy and could be reflected in the national figures. Hence, CBDCs can also significantly ameliorate financial regulation and monetary policy through evidenced-based policymaking enabled by enhanced data.

Disintermediation of private banking and other challenges

However, the introduction of CBDCs is not without its challenges. One important concern arising from CBDCs relates to the potential transition from commercial banking. This relates to accounts-based models. With commercial transactions being undertaken through CBDCs, individuals and businesses may reduce deposits in commercial banks, increasing the volatility of deposits. Given that customer deposits are increasingly important for commercial banking services, CBDCs may threaten banks’ profitability.

Specific CBDC platforms have also absorbed some of the services private-sector financial institutions offer, such as e-transfers, mobile money, or digital wallets. Nigeria’s e-Naira, for instance, allows for a range of services that were once under the purview of private banks, namely diaspora payment, transfer of government aid to citizens, contactless payment, peer-to-peer payment, foreign exchange transactions, or renewal of television subscriptions and purchase airtime, among others. In order to mitigate such risks arising from their disintermediation, commercial banks may adopt a range of measures, including reduced lending, higher costs of credit, and higher costs of ancillary services. These, in turn, could significantly impact small businesses, especially when 72% of MSMEs in Sub-Saharan Africa and 80% of MSMEs in the Middle East and North Africa experience some financing gap. On the flip side, with the potential disruption to traditional banking models, commercial banks may be encouraged to explore new business models and innovate so as to retain competitiveness.

Cybersecurity threats and data protection are imminent risks that governments need to consider. If any vulnerabilities in the infrastructure and system are taken advantage of, these could potentially jeopardise an entire country’s financial system. In early 2022, DCash, a CBDC introduced in the Eastern Caribbean, hit technical glitches that forced the system offline for weeks. Thus, any CBDC being designed by national governments needs to be done in light of the challenges and threats that could potentially arise. Nonetheless, the cybersecurity risks associated with CBDCs can foster a payment landscape characterised by greater security and trust in transactions with the development of robust security frameworks and the adoption of best practices.

Moreover, CBDCs also pose concerns regarding the anonymity of transactions. The anonymity of transactions is an essential feature of cash which enables individuals and businesses to conduct transactions while their identities and personal information remain protected. Nonetheless, it is important to ensure that the payment landscape is also secure and transparent. The implementation of CBDCs also requires the design of robust legal and regulatory frameworks that effectively balance the need for privacy and confidentiality and risks against fraudulent activities, especially as it relates to anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing regulation.

Considerations for the Mauritian Government

CBDCs have the potential to revolutionise the global payment landscape. In the African context, CBDCs could hold potential solutions for increasing intra-regional trade, especially by facilitating transactions and reducing transaction costs. Mauritius, as the gateway to Africa, is in a unique position to take advantage of the opportunities brought about by the nexus of continental free trade and technological advances in payment systems. As the Mauritian Government explores the possibility of introducing CBDCs in the domestic payment landscape, it will need to weigh the potential benefits and consider the necessary reforms and upgrades required in infrastructure and technology, as well as the current regulations. Moreover, the critical role that private banking and financial institutions play in the domestic financial ecosystem must be considered and ensure consistent engagement with such stakeholders to assess the modalities for deploying CBDCs and the role that these institutions will play in a new payment ecosystem. The seamless integration of CBDCs in payment systems that ensure interoperability with existing payment infrastructure will facilitate the update of the digital currency and provide convenience to users. Citizens’ uptake of a digital currency would also require outreach and sensitisation activities to build confidence in converting to the new currency. Moreover, the Bank of Mauritius should consider the lessons learned from regions that have already launched CBDCs or are conducting pilot programmes.

[1] Nigeria was the first African nation to launch a CBDC, the e-naira, making it the second CBDC to have been officially launched worldwide.

Main photo by Behnam Norouzi on Unsplash.

Charles Telfair Centre is an independent nonpartisan not for profit organisation and does not take specific positions. All views, positions, and conclusions expressed in our publications are solely those of the author(s).